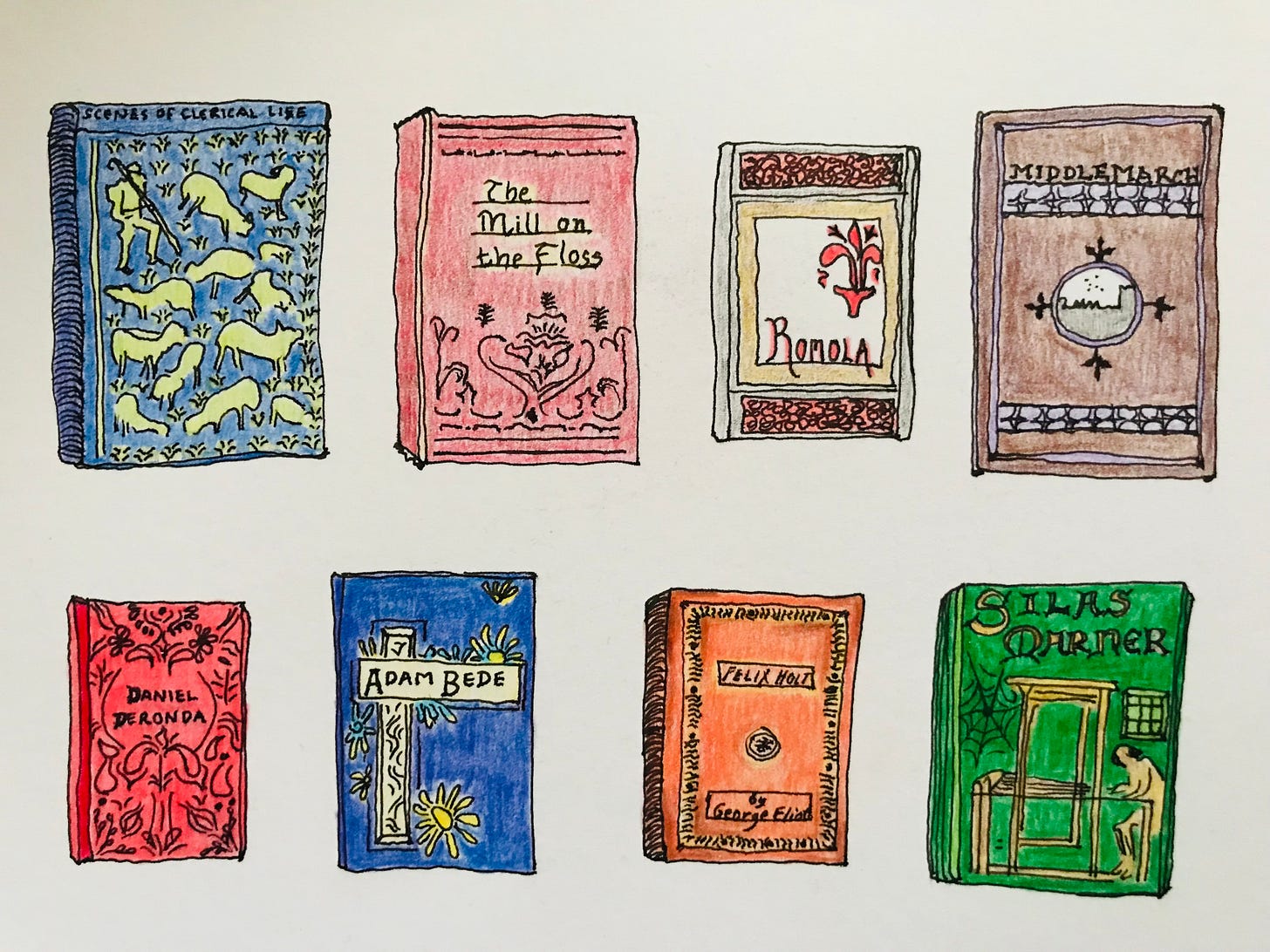

“A man is seldom ashamed of feeling that he cannot love a woman so well when he sees a certain greatness in her: nature having intended greatness for men.”

- George Eliot, Middlemarch

In 1941, McCall’s magazine named Katharine Hepburn its “Woman of the Year.” A film was released the following year, starring her, in which she is singled out and honored for being America’s Outstanding Woman of the Year—Hepburn’s friend Garson Kanin had developed the idea with her in mind. By the time MGM picked it up and production rolled around Kanin had been drafted—fighting the war he would live to document in the 1945 war ministry-produced account of the Allied invasion. Michael, brother of the more famous Garson, was called in to write the script with Ring Lardner Jr., later one of the Hollywood Ten.

Woman of the Year (1942) begins, inauspiciously, in a bar where three ordinary-looking men are listening to a radio broadcast of a baseball game. To any old-movie-watching novice the star Spencer Tracy would be indistinguishable from the supporting cast of daytime bargoers. We’re surprised when the camera lingers on him—tie askew and hat jauntily perched over an equally lopsided face—and he emerges as the love interest for the most beautiful woman in cinema. (The real Hepburn, by the way, found the married Tracy “irresistible.” They carried on a public affair for many years on and off-screen until his death in 1967.)

Sportscaster Sam Craig (Tracy) and political correspondent Tess Harding (Hepburn) clash over the relevance and feasibility of baseball in a war-wrenched America—he thinks it’s indispensable (but can’t coherently explain why or the rules by which the game is played) and she thinks it’s a “frightful waste of energy” during a time that demands all our energy (but has never been to a baseball game). He goes to confront the contentious sports-ignorant polyglot reporter who’s telling everyone what to think in the daily newspaper and he finds Katharine Hepburn, elegantly inspecting her hose in their editor’s office. The attraction is palpable, a swift courtship ensues—a swift, chaste courtship operating under Hollywood’s stringent moral guidelines—and a brief sparsely-attended ceremony unites the pair after which all members disperse to get back to work.

Woman of the Year is billed as a comedy. Sam and Tess’s first outing to the ball game is an homage to “Who’s on First?”; Sam crashes one of Tess’s feminist speeches, ineptly taking a chair behind her on stage and struggling with the fringed dress of his neighbor; their wedding night is interrupted by a war refugee Tess is sponsoring and his train of eastern European henchmen.

But Woman of the Year is really a drama, and the very same slapstick elements can be read as tragic. (For what writer of a slapstick comedy would name the protagonist Tess Harding, ostensibly for Hardy’s tragic heroine Tess? There must be an element of tragedy.) In this light, Sam detracts from Tess’s speech-giving with juvenile antics that make him the center of attention. Tess is giving a speech in honor of her aunt Ellen Whitcomb—her feminist inspiration and surrogate mother, an unmarried woman toward fifty who put her career before marriage, but who later weds Tess’s widower father in a moving ceremony. Ellen is the woman who helped Tess become Tess. It is a serious speech. While it’s playing, we think the scene is slapstick. But upon revisiting it we can see the beginnings of the failure of the marriage that has not yet taken place. It contains the seeds of a sadness that starts to grip them. When something that is important to one partner is not important to the other, a marriage can’t thrive.

So the slapstick ending of the film—the rewritten, writer unsanctioned, studio ending—is not appropriate, illuminating, or funny. It is not the ending Michael Kanin and Ring Lardner wrote.

These two independent workers have struggled to find freedom in commitment, accord in disagreement, excitement in each other's successes. The tension mounts: sturdy Sam becomes stony, confident Tess, feeling unloved and perceiving resentment, falls prey to insecurity. The final scene of the official cut sees Tess try to win Sam back with breakfast in bed. Her stylish top is painfully out of place in Sam’s kitchen—a bachelor’s sterile and intensely unapproachable kitchen. Her waifishness, once dapper, now seems meek. There is no music, no joy. “She does some very improbable things,” Lardner said in a 1996 interview. “It’s improbable that she doesn’t know anything about cooking an egg or making coffee. It was done more for laughs than anything else and it had the effect of saying she was overboard in being a career woman. In effect, it was saying that a woman’s place is in the home.” So the uncredited John Lee Mahin, the writer hired by producers to cut Hepburn’s character down to size, writes an ending where Tess gets her “comeuppance for being too strong in a man’s world,” as Lardner devastatingly put it.

It’s a funny feeling to really love the first eighty minutes of a ninety-minute film and absolutely detest the final ten. We sat through the “fixed” ending with gritted teeth. My mom, in the true spirit of homeschooling, suggested that together we rewrite the final scene and produce it as a radio play—with me doing my Waspy Mid-Atlantic Katharine Hepburn voice, of course. (My vocal exercise for this accent is “My, that yacht is yar!”)

The original ending exists only as a screenplay, and a great one. In a world where the producers controlled the medium it was too keen and too subversive. Earlier in the film an important scene takes place: before his marriage, Sam betrays his real feelings of inadequacy to Aunt Ellen. “I like people. I like meeting and writing about them,” he tells her. “They’re pretty unimportant people and I guess that makes me unimportant.” Kanin and Lardner’s original ending reengages Sam’s nagging worry, illuminated by his wife’s efflorescence, that he is unimportant. He visits a language school, spending a dozen hours trying to learn French and Spanish so he can hobnob with Tess’s high-powered international friends. With Sam missing, Tess covers an important boxing match for him, where the boxers speak the only language she doesn’t know (“They turn in the towel, an’ it wuz on’y a gash over the right peeper...Sweat dat lard off yer basket. I ast for a welter...I get bantams, feathers, flies…!”).

It’s like a 1940s “Sandy and Danny meet halfway at the fair” moment. Sam realizes that Ellen’s earlier response to him was perfectly right: Your work “makes you a very important guy, Sam,” she says. “Not because you have a byline but because you have a heart, a job you like to do, and a future.” Tess realizes that what she does is not the most important thing to do; there are lives worth living that look nothing like hers. There is a true resignation of hubris rather than a depressed domestic defeat.

I think George Eliot would have approved. Rebecca Mead—in a startlingly insightful chapter in My Life in Middlemarch about her own marriage, Eliot’s historical relationship with George Lewes, and Dorothea’s fictional marriage to Casaubon—writes that “the necessity of growing out of such self-centeredness is the theme of Middlemarch.” In Middlemarch, “Eliot shows her reader that marital incompatibility is not simply a matter of one person being misunderstood by another—which is certainly how it can feel, when one is aggrieved and resentful—but that incompatibility consists of two people failing each other in their powers of comprehension.”

If Eliot’s literature is aimed at “generating the experience of sympathy,” as Mead writes, then the original ending in which Sam attempts French and Tess enters the boxing ring is a literal exercise in the experience of sympathy, a word now tenuously connected to Eliot’s Victorian interpretation: “When Eliot and her peers used the word, they meant by it the experience of feeling with another person: of entering fully, through an exercise of imaginative power, into the experience of another.” The difficulty in marriage, then, is realizing the other person is having difficulty, not being the perfect wife or husband.

The true ending of Woman of the Year, as I will now call it, leaves us with the impression that their best work is yet to come as they fashion a working life within a domestic life. Tracy and Hepburn would reunite as lovers eight more times over the next twenty years. They made some of the finest films of their careers together, including Adam’s Rib (1949, dir. George Cukor) and Desk Set (1957, dir. Walter Lang). As Mead writes of George Eliot’s period of loving companionship with Lewes—during which time she wrote all eight of her major novels—“her best work began in being beloved.”

Oy vey! We didn’t get to Gillian Beer, a “Woman of the Year” for many young women scholars. I think a Part Three is in order. Next time I might write about Beer’s time at Cambridge and her pre-Cambridge schooling under the fascinating Robert Bolt (screenwriter of Lawrence of Arabia, Dr. Zhivago, and The Mission, to name just a few).