“My day passes between logic, whistling, going for walks, and being depressed,” Ludwig Wittgenstein wrote when he was living in Norway just before the First World War. His pithy summation of his social calendar might seem bleak. But it sounds a lot like what I do every day, and I’m quite content. Wittgenstein’s “logic” is just a byword for hard work, and I’ve got plenty of that; I whistle big band tunes when joyful or contemplative, to the chagrin of my whistling-averse family; dog walks occupy an inordinate amount of my day; and a touch of depression is reasonable.

Wittgenstein is not literally my friend, of course, but I am reading Ray Monk’s philosophical biography of him, The Duty of Genius. It’s part of my ‘Wittgenstein and Melville’ unit that began with reading Moby-Dick. I’m reading some biography and some criticism to help orient me before we start the Tractatus, the hard stuff. I’m reading One Foot in the Finite: Melville’s Realism Reclaimed, a Wittgensteinian reading of Moby-Dick, with the author—who just so happens to be my mom. What joy to be able to ask her what she meant by this line or other!

On my first approach, the unapproachable Wittgenstein seems, in a word, Austrian. A telling example: Wittgenstein’s friend and mentor at Cambridge (before his philosophical schism) was Bertrand Russell. Wittgenstein was sick of Cambridge, sick, he said, from lack of oxygen. (Where is there more oxygen than Norway, with only five people breathing it?) Wittgenstein set his heart on doing his work there. Russell warned him of the torpefying cold and solitude of the place: “I said it would be dark, & he said he hated daylight. I said it would be lonely, & he said he prostituted his mind talking to intelligent people. I said he was mad & he said God preserve him from sanity. (God certainly will.)” Wittgenstein is funny, in the German sense, komisch. He’s melodramatic, but somehow not affected—this is how he sees the world.

His interests brought him from Vienna to prewar Cambridge, where his highly-cultured sensitivities mingled with his attractive roguishness made him the darling of Russell’s circle. But he had no patience for English bureaucracy. This is the letter he wrote to G. E. Moore about his early masterwork, the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, not being a suitable substitute for a bachelor’s thesis, according to the regulations:

“Dear Moore,

Your letter annoyed me. When I wrote Logik I didn’t consult the Regulations, and therefore I think it would only be fair if you gave me my degree without consulting them so much either! As to a Preface and Notes; I think my examiners will easily see how much I have cribbed from Bosquanet.—If I am not worth your making an exception for me even in some STUPID details then I may as well go to HELL directly; and if I am worth it and you don’t do it then—by God—you might go there.

The whole business is too stupid and too beastly to go on writing about it so—

L.W.

Wittgenstein has an emphasis problem: he adores italics, maybe too much. All his letters are aposiopetic—readers lurch through sentences abruptly broken off. His snappishness is set off by em dashes.

But you see what I mean, right? Austrian.

On the other hand, though he may not have trumpeted the fact, he was also fundamentally Jewish. He was born into one of the most prominently wealthy Jewish-Viennese families of the era. He later abdicated all his inheritance, spurned the attention of his siblings, and nominally became a Christian. But, as a Jew reading in a strange and upsetting time for Jews, I see in his writing an impulse to speak (and hear) only the truth. This addiction to honesty seems to me intrinsically Jewish, and something we can’t abdicate or convert.

For all Monk’s perception, logical and philosophical understanding, rigorous research, and fine writing, Wittgenstein’s Jewishness is what he misses. Yes, of course there is much on Wittgenstein’s Jewish background, how he may have hid it from his friends, and the inevitable intersection of his life with the rise of Nazi Germany and an inhospitable Austria. But there doesn’t seem to be an established link between Wittgenstein’s Jewishness and his philosophy.

Ray Monk is a lovely man, a Brit. Once at a conference my mom met him. I was a toddler and for some embarrassing reason, in need of underwear. Monk himself lent me a pair that belonged to his daughter. They were my favorite for a long time, actually. Only now am I beginning to grasp the full significance of these undergarments!

But to return to the matter of Ray Monk’s Britishness, which I suspect is key to understanding The Duty of Genius. What Monk describes as “Wittgenstein’s chronic sensitivity,” the behavior that so annoyed Wittgenstein’s Cambridge colleagues, was perhaps Wittgenstein’s incapacity for not telling the truth. “There is no wall between you and your fellow men,” his friend Ludwig Hänsel remarked. “I have a thicker crust around me.” Wittgenstein is “sensitive” because he doesn’t build up this crust around him. He is exposed, at once vulnerable and percipient—he feels everything and he wants to talk about it. This is not the phlegmatic British way!

But Monk gets to the heart of what it means (to me, at least) to be a Jewish thinker, even though he didn’t mean to:

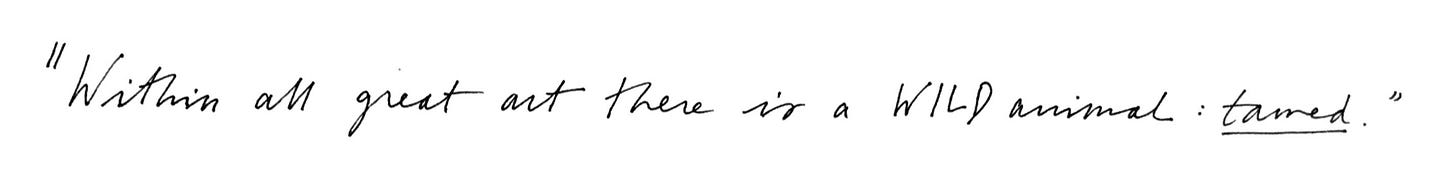

[Wittgenstein] often remarked that the problem of writing good philosophy and of thinking well about philosophical problems was one of the will more than of the intellect—the will to resist the temptation to misunderstand, the will to resist superficiality. What gets in the way of genuine understanding is often not one’s lack of intelligence, but the presence of one’s pride. Thus: ‘The edifice of your pride has to be dismantled. And that is terribly hard work.’ The self-scrutiny demanded by such a dismantling of one’s pride is necessary, not only to be a decent person, but also to write decent philosophy. ‘If anyone is unwilling to descend into himself, because this is too painful, he will remain superficial in his writing.’

The point, Monk explains, “was not to hurt his pride, as a form of punishment; it was to dismantle it—to remove a barrier, as it were, that stood in the way of honest and decent thought.” Wittgenstein purposefully chose students that were extremely bright, innocent in the sense that they hadn’t yet developed the pride-edifice. And he expected his friends, even his mentors, to undertake the same effort. When they didn’t (or couldn’t) he was surprised and disheartened.

An aside or an illustrative example (Wittgenstein was always calling for and supplying illustrative examples!): This impulse takes shape in Abe Ravelstein, Saul Bellow’s character molded from the real-life Allan Bloom, philosopher king of Chicago and Bellow’s close friend. In Ravelstein, Bellow’s final novel—the literary biography Bloom essentially commissioned before his death—professor Ravelstein thinks the ability to write and read well, a man’s “seriousness,” is inextricably linked to his “willingness to let the self-esteem-structure be attacked and burned to the ground.” He maintains that “a man should be able to hear, and to bear, the worst that could be said of him.” Again, the point is to clear the vision for thinking.

What I mean by Wittgenstein’s “Jewishness” is a separate matter from either his religion or his philosophical interest in religion. As he once remarked to his student and friend Maurice Drury, “If you and I are to live religious lives, it mustn’t be that we talk a lot about religion, but that our manner of life is different.” Wittgenstein doesn’t strike me as Jewish in the sense that he was observant in any typical way. But rather because he did not tolerate untruths; because he said the things that are hard to hear; because his introspection took the form not of rumination but of self-scrutiny.