The past several weeks of my schooling have been occupied with work most unlike my usual schooling. Reading and writing and discussion have become purely personal endeavors for a time. Instead, I’ve been tinkering—measuring, modeling, hammering, planing, sanding, sawing. I say tinkering because of my amateurishness at carpentry and woodworking, and because it’s one of those words that sounds exactly like what it means. The clatter of syllables in tinkering somehow conveys the bits and bobs you’re working with, all knocking together; the tedious, persnickety operations of the hands.

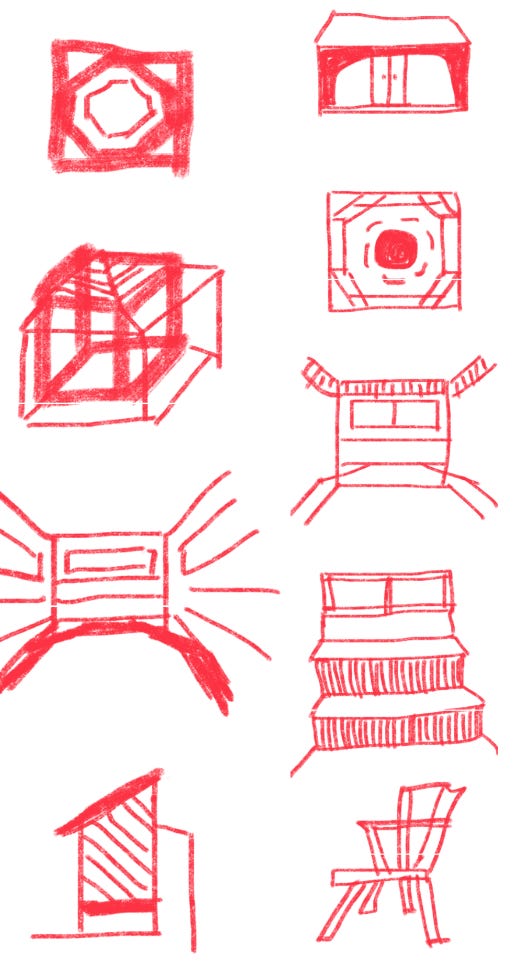

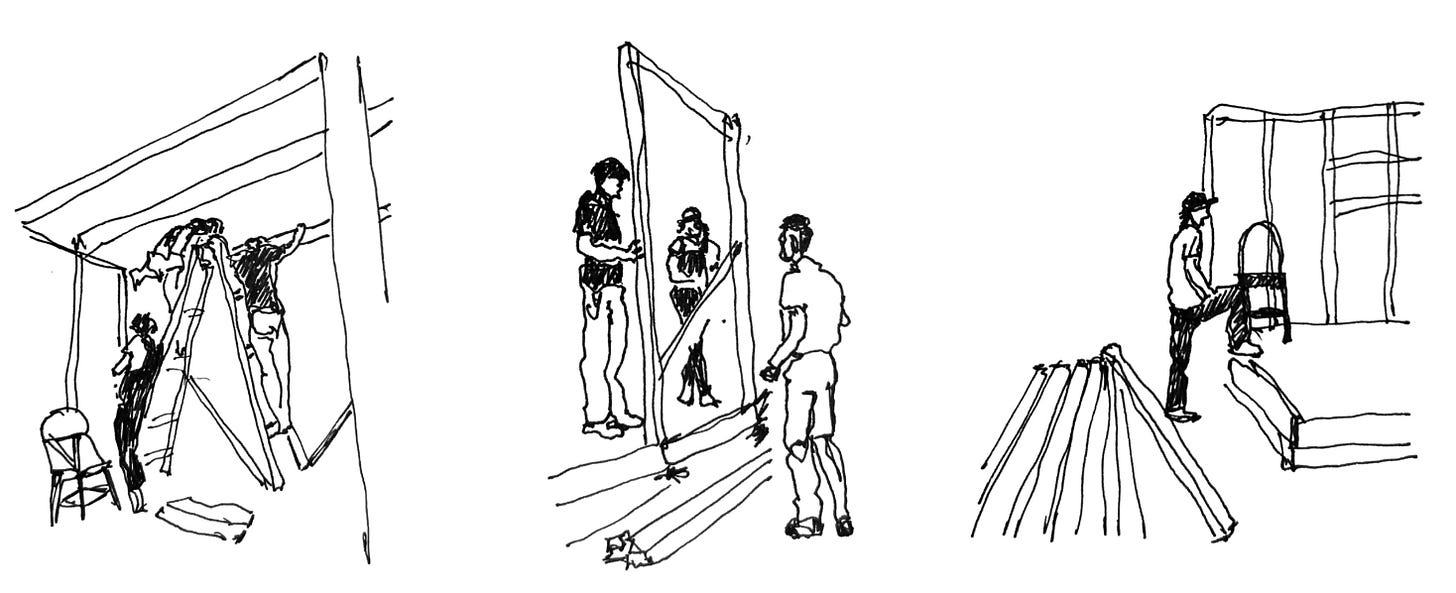

In one class, I’m building an eight-by-twelve foot building, a vernacular structure made mostly from materials found around campus, designed to be a place of religious significance. But unlike the Tabernacle (one could say the original “vernacular structure”!), we’re working with modest means, not the jasper, rubies, goat’s hair, and acacia wood of the Old Testament. We are working with pallets, buckled and bleached from years in the desert; frosted glass, leftover from some uncompleted project taken up by students long graduated; and cement blocks for marking parking spots now make the foundation.

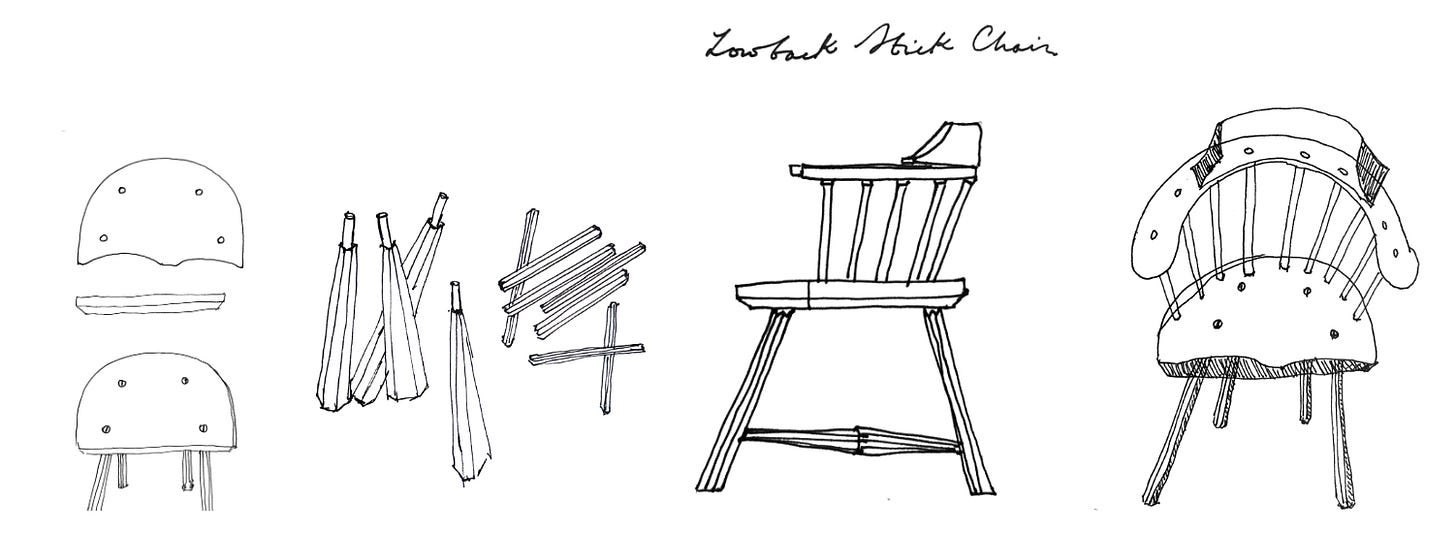

In another class, I’m learning to hand-craft a Windsor-style chair. It’s far from simple. Every curve, flat surface, mortise and tenon, is earned. In the woodshop, which feels like it was perniciously designed to hold heat in the mid-afternoon, I sweat so much my safety glasses slip off my nose. I rasp my corners so viciously I get blisters. And, in a moment of tiredness and foolhardiness, I thrust a rather large piece of wood into my face in an attempt to take it off its pegs. Dazed, I stumble out of the woodshop and cry for help until I realize no one is coming to help me. So I start walking to get help for myself, blood dripping from my nose and into the dust at my feet. (A lesson I keep learning at college—no one is coming, so I must start walking.)

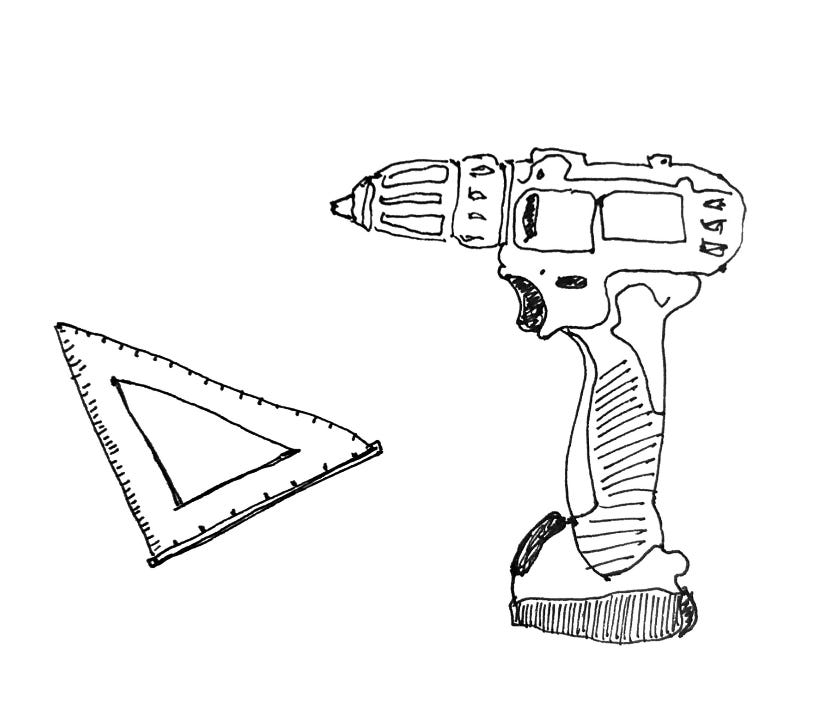

I am building on the large scale, and the small. I am helping to build something for a community, and something that can only ever hold one person at a time. I am learning the value of brute force (sometimes you just have to knock a beam into place with a thwack of the hammer) and of gentle pressure (lest the wood you’ve carefully sawn and planed and sanded snap in two). I am learning the value of terminology—drill versus driver, Phillips versus star, bevel gauge, spokeshave, dozuki saw—and the value of ‘Hey, hand me that, will you?’

There is the satisfaction of a tapered chair leg fitting in a mortise drilled at exactly the right angle. And there is the satisfaction of walking up to the swimming hole, passing our structure, fully framed, waiting for us to sheathe it tomorrow. It is the first time I’ve seen it out of the burning midday sun. It has taken on a completely different character in the twilight. It doesn’t seem like a skeleton in the wasteland. It seems as though it has always been there, and it always will be.