My fourteen weeks of intense study of Heidegger’s corpus have come to an end. Maybe not the most appropriate choice for a freshman, or a first philosophy class! But nevertheless an inciting, inflaming start to a study of Western philosophy and the ancients. My first essay for this class was a reproof of Heidegger for being such a poor reader of Plato. (I was a little transparently angry about Heidegger’s warped translations of The Republic!) So I spent much of the rest of the course trying to see what Heidegger was really saying about Plato—what he was really saying about the West, that is—behind the vagaries and etymologies and tautologies.

The question of what the West is is especially alive for me right now as a college freshman trying to figure out what to study and why. I just love old books, and at college they expect you to either justify or reject that impulse.

In his Introduction to Metaphysics, Heidegger poses what for him is “the question”: “Is ‘Being’ a mere word and its meaning a vapor, or is it the spiritual fate of the West?” Often acting as his own interlocutor, he goes on to circuitously disprove that Being is a mere word and its meaning a vapor. “Being is completely different from vapor and smoke,” Heidegger concludes one hundred pages later, using one of Parmenides’ epigrams to aid his interpretation. Heidegger expects us to have kept his starting question in mind: from the negation of the first clause of his question, we must infer that, for Heidegger, Being is the spiritual fate of the West. But what is the West?

How can readers of Heidegger today have a profitable discussion of the West if they proceed, as many likely will, under the assumption that “the West” is a fiction? For Heidegger, the West is decidedly not a fiction—it is simultaneously distinct and shapeless, as real and fugitive as Being itself. Answering the question of what Heidegger means when he writes “the West” or “Western philosophy,” then, is not so simple as tendering a worn phrase: the tradition which began with the Greeks.

Heidegger’s conception of the West is most often viewed chronologically. In other words, Western philosophy is seen in Heidegger’s thought to be the movement from the pre-Socratic through the later Greeks, the Roman translation, the Christian mutation in the Middle Ages, and upwards through modernity down to us. But thinking of Western philosophy in this way places the most originary thinking at the farthest remove from us. A chronological account of the West, the history of Western philosophy, lends itself to a doxographical account of philosophy, which, Heidegger rightly asserts, irons out all the difficulties of philosophy. “Philosophy, in its inception, did not tie itself down to particular propositions. It is true that the subsequent accounts of its history give this impression, for these accounts are doxographical, that is, they describe the opinions and views of the great thinkers.”

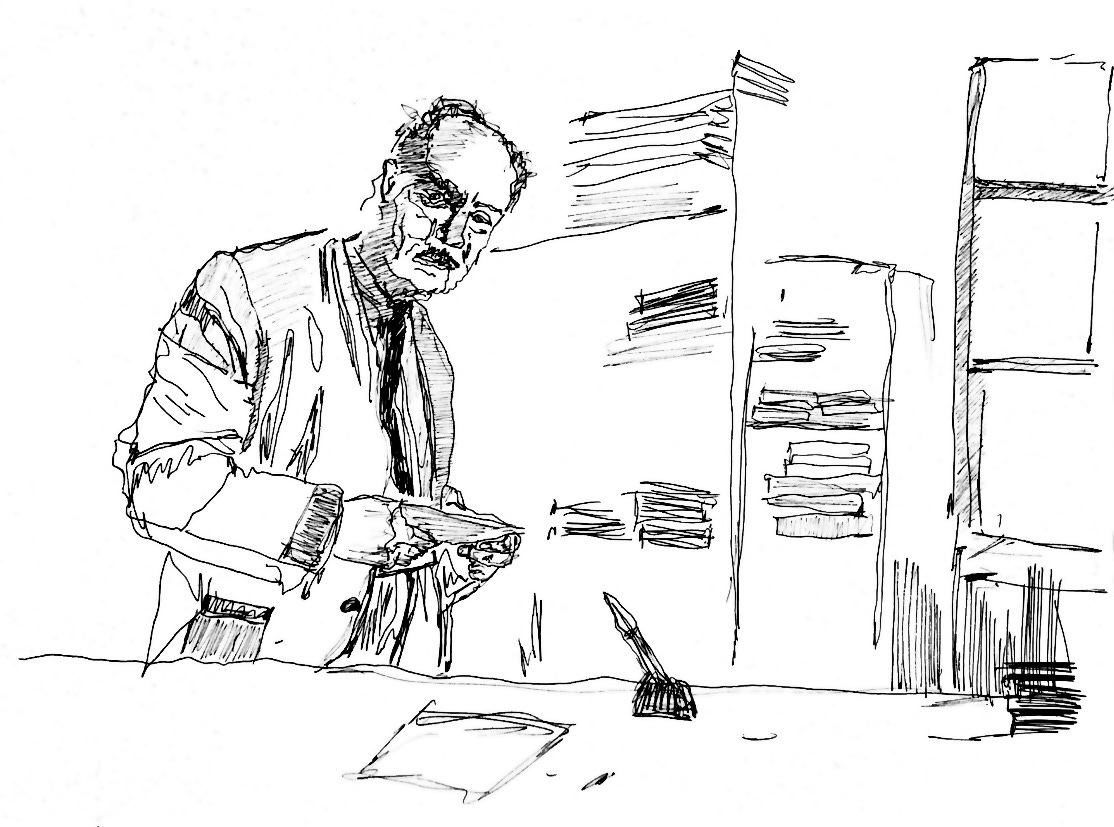

This is the impression of the West we have today—a series of propositions, arguments, tenets, handed down from ancient to modern. “But whoever eavesdrops on the great thinkers and ransacks them for views and standpoints,” Heidegger continues, “can be sure of making a false move and taking a false step.”

When we think of the West and the history of Western philosophy as chronological or doxographical we are setting ourselves up to forget its inception. “This inception,” Heidegger writes, “is taken as something that we have left behind long ago and supposedly overcome.” What is inceptive should be the closest to us, the object of our keenest questioning, but thinking of the philosophical tradition in the West as something merely chronological makes it seem like an imperative to snuff out that which is too old and far from us to be of any account.

“All essential questioning in philosophy necessarily remains untimely,” Heidegger maintains, “because philosophy either projects far beyond its own time, or else binds its time back to this time’s earlier and inceptive past.” Mere chronology does not establish meaningful unity. “Philosophizing always remains a kind of knowing that not only does not allow itself to be made timely, but, on the contrary, imposes its measure on the times.” To be made timely is to be bound to time, to be limited to the particular time in which something happened to have been written. When Heidegger calls philosophy “untimely” he does not mean that it is irrelevant. On the contrary, he means that philosophy is always both of the times, speaks to the present moment, and timeless in the sense of belonging to no time in particular.

But Heidegger is also saying something even harder to hear about timeliness. “Philosophy is essentially untimely because it is one of those few things whose fate it remains never to be able to find an immediate resonance in their own time, and never to be permitted to find such a resonance.” Philosophy, because it is not ‘in measure with the times’ (zeitgemäß), is uniquely susceptible to the accusation of irrelevancy.

The philosopher’s fate is always to be at the periphery, building his academy outside the city walls. But it is good for philosophy to be pushed to the borders because “whenever a philosophy becomes fashion, either there is no actual philosophy or else philosophy is misinterpreted and, according to some intentions alien to it, misused for the needs of the day.”

Heidegger’s philosophy did become a fashion and it was misused for the needs of the day. While Heidegger claims that Plato lets us forget the meaning of Being by not explicitly questioning it, thus leaving it too open to misinterpretation, Heidegger’s work is itself open to misinterpretation, as any writing worth reading is. Heidegger and his unique view of the West have been taken up by subsequent voices as a means to furthering ends. Reading Heidegger charitably means acknowledging the difference between what Heidegger actually writes, and writes deliberately and reservedly, and how he is taken up in academic contexts. Heidegger’s view of the West in decline is most popular among contemporary scholars at pains to make the works associated with the West irrelevant, at the same time that his idea of a return to the inceptive West finds traction with far-right movements eager to establish a lineage between the culture of Athens and central Europe. Neither of these readings are conducted in the spirit of genuine philosophical inquiry, or what Allan Bloom in his book Giants and Dwarfs calls “taking tentative but ever surer steps toward understanding authors as they understood themselves.” Both have the effect of shutting down the West where Heidegger had intended to open it up.

Leo Strauss, once the student of a young Heidegger at Freiburg, was one philosopher who found a fruitful opening up of the West in Heidegger’s thought. “The single advantage of the total crisis of philosophy,” Bloom writes in his encomium to his teacher Strauss, “was that it permitted a total doubt of received philosophic opinion that would have been considered impossible before.” That is, Heidegger’s commitment to showing that the history of Western philosophy has been bankrupted by the gradual forgetting of Being allowed Strauss and others to return to the roots of Western philosophy in an attempt to uncover what had long been covered over.

Acknowledging the decline of the West had the opposite effect of nihilism for Strauss; it had the effect of showing just how necessary an understanding of the earliest thinkers is. A clear-eyed reader of Heidegger, Bloom characterizes Heidegger as working “to dismantle the Western tradition of rationalism in order to recover the rich sources out of which rationalism emerged but which had been covered over by it.” So an effort of recovery, testing the contemporary assertions, was necessary for Strauss, as Bloom writes. Students of Heidegger know that “recovery means discovery,” and to discover is to find anew, to dis-cover what has been covered over, the attempt to throw off whatever covering has cloaked the thing in question.

In the intervening millenia since the first rumblings of philosophy in the West a tradition has developed which ceases to take its claims to truth seriously, Bloom writes. Thus, Strauss concludes with Heidegger, “to begin again from the natural beginning point is even more necessary today.”

What does it mean to begin again from the natural beginning point of Western philosophy? Why does it matter to us? Or, as Heidegger asks, “What use, then, is the multifaceted and complex history of Western philosophy, if they do the same thing anyway? Then one philosophy would be enough. Everything has always already been said.” Reading Heidegger generously means recognizing this question for what it is: rhetorical. He continues: “And yet this ‘same’ possesses, as its inner truth, the inexhaustible wealth of what is on every day as if that day were its first.” For Heidegger, Western philosophy is not chronological or doxographical—it is not even really about Europe or Germany.

The West, for Heidegger, is the tradition that emerged from the inceptive texts, texts written to see things as if for the first time, texts engaged with deconcealment and the essence of truth—texts which are inexhaustible, which see everything stale afresh. The West is recovering those texts which have been covered over and need to be dis-covered. In the attempt to dis-cover what those texts are really saying one comes to actually practice philosophy.

For Heidegger, philosophy means asking the hardest, most irresolvable questions and never setting them aside. Philosophizing in the Western tradition is “venturing to exhaust, to question thoroughly, what is inexhaustible.” The texts which we are questioning are incapable of being depleted. The decline of the West is only the drained appearance of sameness; the inceptive texts, read and questioned more and more “originarily,” as Heidegger would say, are inexhaustible.