Yes, I’m still thinking about Cleopatra this week. Mind you, I don’t yet have a cast for Antony and Cleopatra. I’m imagining actors who haven’t auditioned for a play I haven’t gotten clearance to put on. But even if it never materializes, thinking about putting on this play is its own kind of study (ungraded and unpolicied, my favorite kind).

In Shakespeare’s play, Antony and Cleopatra seem perfectly aware of their roles as actors—actors in the Mediterranean theater of war, dissemblers before audiences of armies and courts and generals and siblings. Cleopatra, upon hearing of Antony’s (Roman) wife’s death, turns to him in a sly attack: “Play one scene of excellent dissembling, and let it look like perfect honor” (I. iii). Antony’s limp response to the news frightens her; if this is how he reacts to Fulvia, how would he mourn her? But her language signals her awareness of Antony’s theatrical capabilities.

Shakespeare capitalizes on the language of acting. Antony accuses Cleopatra of tricking him into abandoning his fleet at Actium: she “false-play’d my glory unto an enemy’s triumph” (IV. xiv). “False-play’d” is easily taken as “betrayed.” But it would be a loss to not recognize the theatrical sense of playing, falsely being someone else. And in the final scene of the play, Cleopatra calls her suicide a “noble act” (V. ii). An action to prove her nobility, to prove her love to Antony, and at the same time, an awareness of her audience witnessing the fatal final act.

As her biographer Stacy Schiff writes, Cleopatra’s line had a “family gift for stagecraft.” She alludes to the preposterously bloody and incestuous history of the Ptolemies, a Greek line of rulers who established themselves as rulers in Egypt a dozen generations before Cleopatra VII came to power. In one theatrical display, Ptolemy XIII (her preadolescent brother) ordered the murder of his ally Pompey the Great. In the brackish waters of Pelusium he was warmly received—and then beheaded, in front of his wife and army.

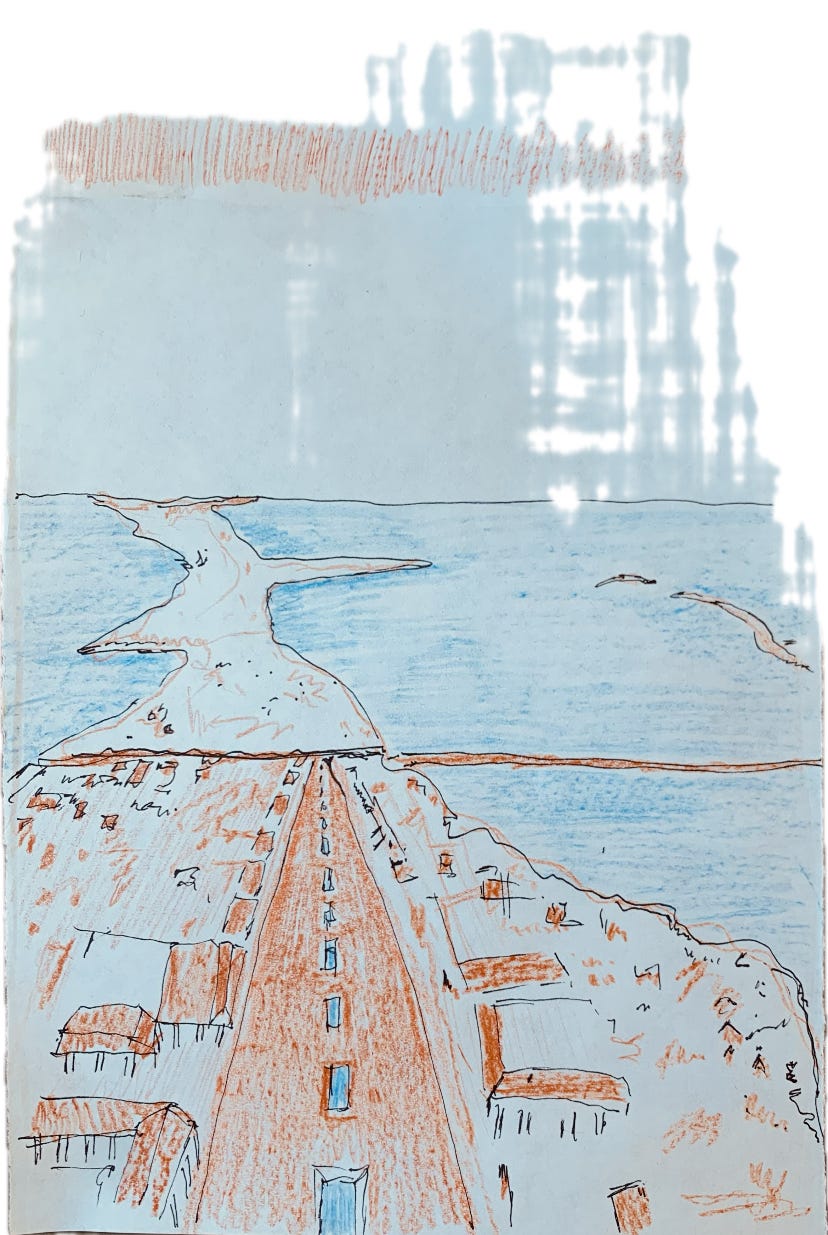

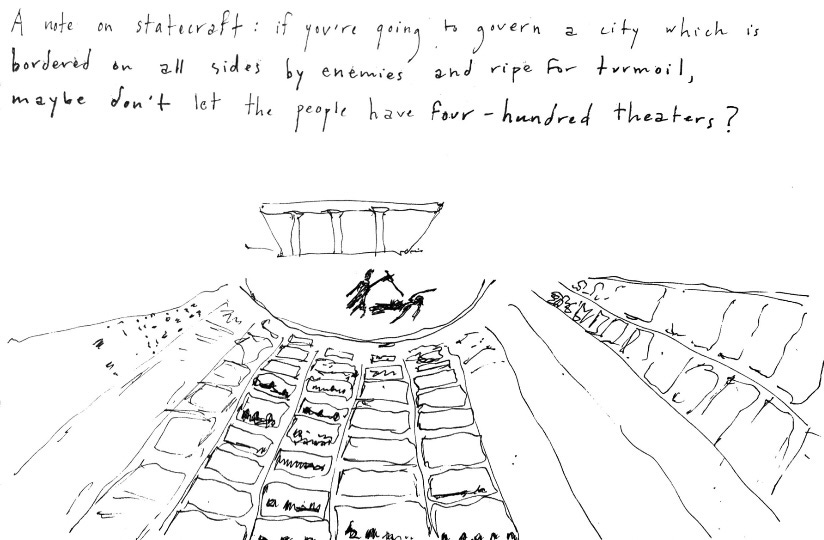

Alexandria, the city Cleopatra ruled for a couple of decades, had a unique character in the 50s and 40s (BC). Schiff describes the ancient Alexandrian populace as possessing a “quick and biting” humor. “They knew how to laugh,” she writes. “They were mad for drama, as the city’s four hundred theaters suggested. They were no less sharp-elbowed. The genius for entertainment extended to a taste for intrigue, a propensity to riot.” (We see how this taste persists into the 1940s and 50s in Lawrence Durrell’s Alexandria Quartet!)

Theater was not just fodder for the masses. An aristocratic Alexandrian’s education revolved around reading the Greek poets and tragedians. Schiff writes that Cleopatra’s lessons would have involved the imaginative treatment of what were already classic works in her time. “She might write as Achilles, on the verge of being killed, or be called upon to restate a plot of Euripides.” Heraclitus, a near contemporary of Cleopatra, wrote that children of her generation were “nursed in their learning by Homer, and swaddled in his verses.” Euripides, Aeschylus, and Sophocles followed close behind. “She would have known various scenes by heart.”

Wonderful! What an education! But perhaps a queen and a people stewing in Greek tragedy might not lead to the most stable or well-functioning state? I just finished Aeschylus’s Orestaia trilogy (comprised of the plays Agamemnon, The Libation Bearers, and Eumenides) and I can’t say that it wasn’t thoroughly disturbing and morally confusing. Like the real life history of the Ptolemaic line, Aeschylus’s magnum opus contains all the -cides you could imagine—fratricide, parricide, mariticide, filicide. And some of the murderers come out looking pretty good.

Theater is dangerous. Greek tragedy is especially dangerous. The Greek theater, according to critic Oliver Taplin, “was particularly non-naturalistic and stylized.” When the poor schmuck in the last row is sixty meters away from the orchestra everything on stage had to be big—the faces (giant masks which actors wore painted into a single expression for the entirety of the play), the gestures (which sometimes required a crane-like contraption to send actors flying on ropes), and the action, heightened to hyperbole.

So how do I reconcile my love for the theater for what I know to be its riotous, disturbing, unmooring, dangerous tendencies? I suspect one way is to act it out, play drama and interrogate it.

There’s a line in Antony and Cleopatra, in the final scene, when Cleopatra seems to be speaking directly to you. It comes as a bit of a shock.

She sees that hers is a story worth telling and that will be told for ages to come. As soon as she is dead—a few pages later—she will start to be represented and misrepresented. “In Rome,” she says to her maidservant, “thou, an Egyptian puppet, shalt be shown.” As characters, people playing at love and war, they’ll take the stage again:

saucy lictors

Will catch at us like strumpets, and scald rhymers

Ballad us out o’ tune: the quick comedians

Extemporally will stage us and present

Our Alexandrian revels; Antony

Shall be brought drunken forth, and I shall see

Some squeaking Cleopatra boy my greatness

I’ the posture of a whore. (V. ii)

Shakespeare’s audience would’ve heard these very lines from the mouth of a pipsqueak boy! But Cleopatra’s Elizabethan writer is no “scald rhymer.” He knows that there will be productions he cannot oversee. So he builds the criticism of the play into the play. Antony and Cleopatra is not a historical depiction of the bacchanalian revels of ancient Alexandria; Antony is not merely a drunken fool; Cleopatra is not merely a seductress. She is an actress.