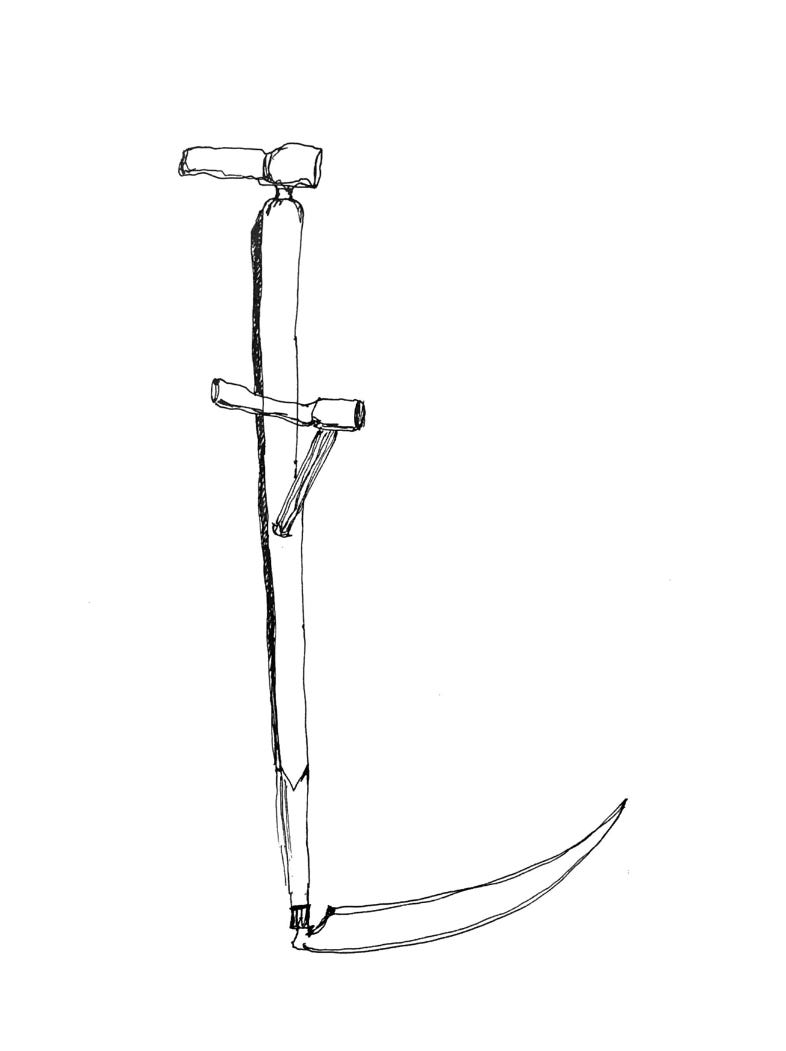

“What are these little white spots on my hands? Do I have some sort of disease?” It was patently obvious that I’d never had calluses when I started doing manual labor a few months ago. Now I’m used to the toughened white bubbles. Keeping track of their progression helps me keep track of time—soft and sore, then dry and flaky, and finally a satisfying little hard sweatless patch. I have a fresh blister today, embossed on my left hand like red irritated stationary. This one’s from scything. Yes, from using the obsolete harvesting device (of Soviet-era Russia and Grim Reaper fame). There’s a peculiar sort of motion involved that I’m getting used to after a few weeks of leveling weeds and tall grasses—a rotation from the hips and shoulders after which the sides of my spine ache, and my hands feel permanently clenched around the handles. The scythe is as tall as me and I hold the blade up to my face when I sharpen it, pressing the whetstone flatly against its face and pulling it into sharpness.

And the best part is that scything keeps popping up! In Far from the Madding Crowd, which I’m reading with delight in stolen snatches, there’s a lovely description of the workers reaping the fields. I suppose it’s not too great a coincidence in a 19th century book about farming! But it still felt significant to me. Bathsheba, the heroine, owns a farm in Victorian Wessex:

A week or two after the shearing, Bathsheba, feeling a nameless relief of spirits on account of Boldwood’s absence, approached her hayfields and looked over the hedge towards the haymakers. They consisted in about equal proportions of gnarled and flexuous forms, the former being the men, the latter the women, who wore tilt bonnets covered with nankeen, which hung in a curtain upon their shoulders. Coggan and Mark Clark were mowing in a less forward meadow, Clark humming a tune to the strokes of his scythe, to which Jan made no attempt to keep time with his.

The women are full of bends and curves, and the men appear twisted and knobbly. I do feel rather flexuous while I’m scything; but afterwards, when the muscles have cooled and stiffened, I become as creaky as these old farmers. Hardy writes about sharpening the tools, too:

All the surrounding cottages were more or less scenes of the same operation; the scurr of whetting spread into the sky from all parts of the village as from an armoury previous to a campaign. Peace and war kiss each other at their hours of preparation—sickles, scythes, shears, and pruning-hooks, ranking with swords, bayonets, and lances, in their common necessity for point and edge.

Going to war in the garden, indeed! Waging a battle of attrition against weeds. But was it just a fluke when Wordsworth’s poem “The Solitary Reaper” was tangentially discussed in my Heidegger seminar today? I’m also in statistics, and I think that counts as an event of interest. “Behold her, single in the field,” it begins, “Yon solitary Highland Lass! / Reaping and singing by herself.” The Gaelic girl “o’er the sickle bending” enchants the speaker, not with her scything technique, I’m afraid, but with her voice “so thrilling ne’er was heard.” Now I can’t claim to be able to hum in tune to the strokes of my scythe like Hardy’s Farmer Clark nor sing plaintive numbers like Wordsworth’s Scottish maiden, but I can scythe like nobody’s business.