In John Williams’ novel Stoner (1965) three graduate students sit around a saloon table drinking and talking. “Have you gentlemen ever considered the question of the true nature of the university?” asks the irreverent Dave Masters. He fixes his penetrating gaze on the eponymous William Stoner. “Stoner, here, I imagine,” he continues, “sees it as a great repository, like a library or a whorehouse, where men come of their free will and select that which will complete them, where all work together like little bees in a common hive. The True, the Good, the Beautiful. They’re just around the corner, in the next corridor; they’re in the next book, the one you haven’t read, or in the next stack, the one you haven’t got to. But you’ll get to it someday. And when you do—when you do—” He breaks off and the aposiopesis leaves Stoner filling in the blank. Stoner “smiles uncomfortably.” Masters’ diagnosis, though delivered impishly, is disturbing to Stoner and he remembers the speech “for years afterward.” That perennial unfinishedness—that unknown objective, broken off and dangling—shapes the story of William Stoner, the earnest, ardent, inward professor of English literature.

Stoner, born to Missouri farmers in the years leading up to the Depression, comes to the university to study agronomy; his head is turned by literature, and the crotchety old professor who teaches it. The required survey of English literature “troubled and disquieted him in a way nothing had ever done before.” He “could not handle the survey as he did his other courses.” In Archer Sloane’s freshman English Stoner can’t get by simply doing his work methodically, like he does his chemistry assignments, “with neither pleasure nor distress.” The class distresses him because “he could not see the use of what he did.” He could not till, sow, and reap the harvests with his own leathery hands. It isn’t that simple anymore.

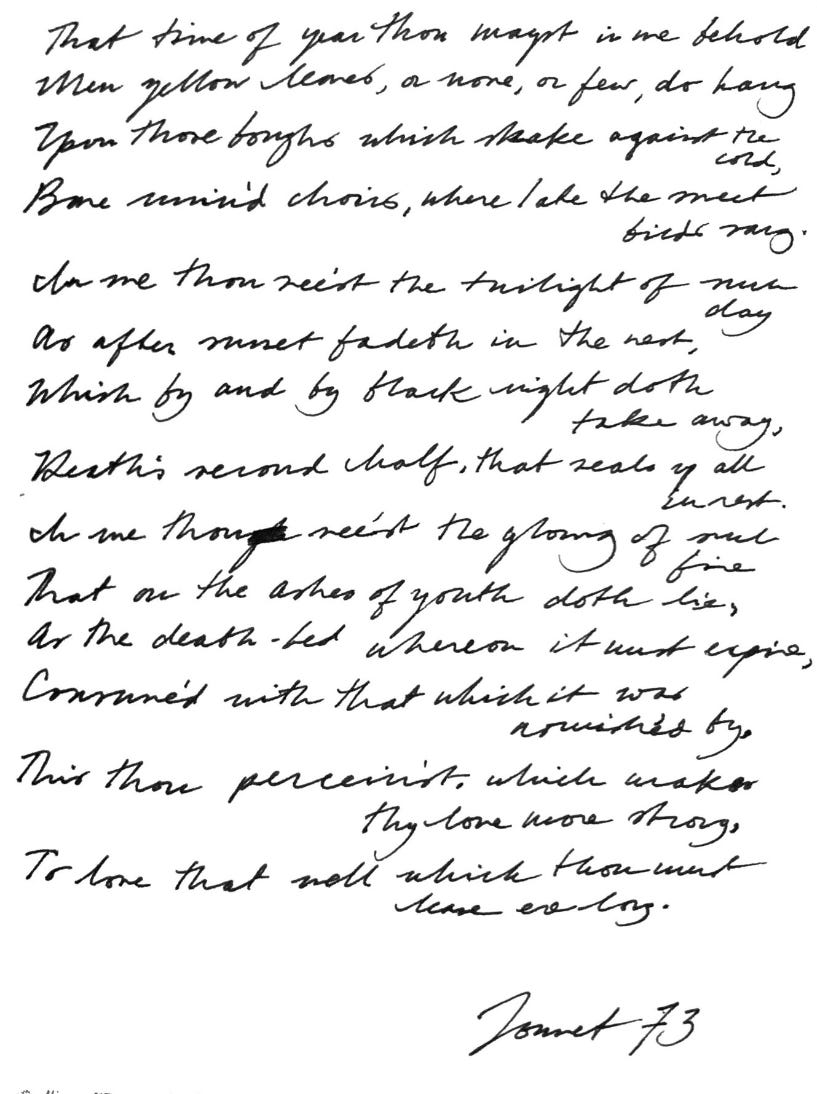

One day in class Sloane asks Stoner what Shakespeare’s “Sonnet 73” means. When Sloane recites it, “his voice deepened and softened, as if the words and sounds and rhythms had for a moment become himself.” Breathless with this new understanding of his cadaverous professor, Stoner struggles: “‘It means,’ he said.” “‘It means,” he said again, and could not finish what he had begun to say.” Class ends abruptly, and Stoner shuffles out. And suddenly the possibility of sitting down and methodically working through textbooks has given way to a new question (What does this text mean?) and a new set of problems (How do I figure it out by reading? How do I go about reading?). “In the second semester of that school year,” Williams writes, “William Stoner dropped his basic science courses and interrupted his Ag School sequence; he took introductory courses in philosophy and ancient history and two courses in English literature.”

Stoner is not successful in the usual ways. On the first page we learn that “Stoner’s colleagues, who held him in no particular esteem when he was alive, speak of him rarely now.” But he somehow manages to escape the hardscrabble clods-of-dirt existence he comes from and avoid the careerism and solipsism that often go along with academic life. His father keels over in the dirt and Sloane expires behind his desk. Instead, as Stoner lays dying, “he felt he was waiting for something, for some knowledge; but it seemed to him that he had all the time in the world.” It is all unfinished, but he is content: “He was himself, and knew what he had been.” He reaches for his book, his monograph on English poetry, and pages through it until “the old excitement” grips him and then finally releases him.