Ten days ago I started reading Moby-Dick. It’s not an easy approach for anyone, but it’s especially weighted for me, since my mom is a Melville scholar and her specialty is Moby-Dick. She’s never pressed it upon me, and frankly I have never been that interested in reading it, but here we find ourselves in the last few months of homeschooling and it seems like the right move. I’m now on Chapter 69, “The Funeral.” But there is nothing funerial about Moby-Dick. It turns out to be hilarious! I’ve been giggling and chuckling to myself, even throughout my ghastly expectorating illness. It’s the kind of book you can shape your life around, like my mom has. With much more to say, here are three surprising discoveries from my first time around.

I. The whale isn’t actually white! Moby-Dick is distinguished by his “peculiar snow-white wrinkled forehead, and a high, pyramidical white hump” while the rest of his body is “so streaked, and spotted, and marbled with the same shrouded hue, that, in the end, he had gained his distinctive appellation of the White Whale; a name, indeed, literally justified by his vivid aspect, when seen gliding at high noon through a dark blue sea, leaving a milky-way wake of creamy foam, all spangled with golden gleamings.” We invest the whale with some of his terrifying whiteness, then, “the expressive hue of the shroud,” with our mortal vision’s propensity to associate the wake with the whale, to heighten the contrast of the whale and the water. How often have you seen a purely-white pearlescent whale in representations of Moby-Dick? They most often look like this one, by Augustus Burnham Shute:

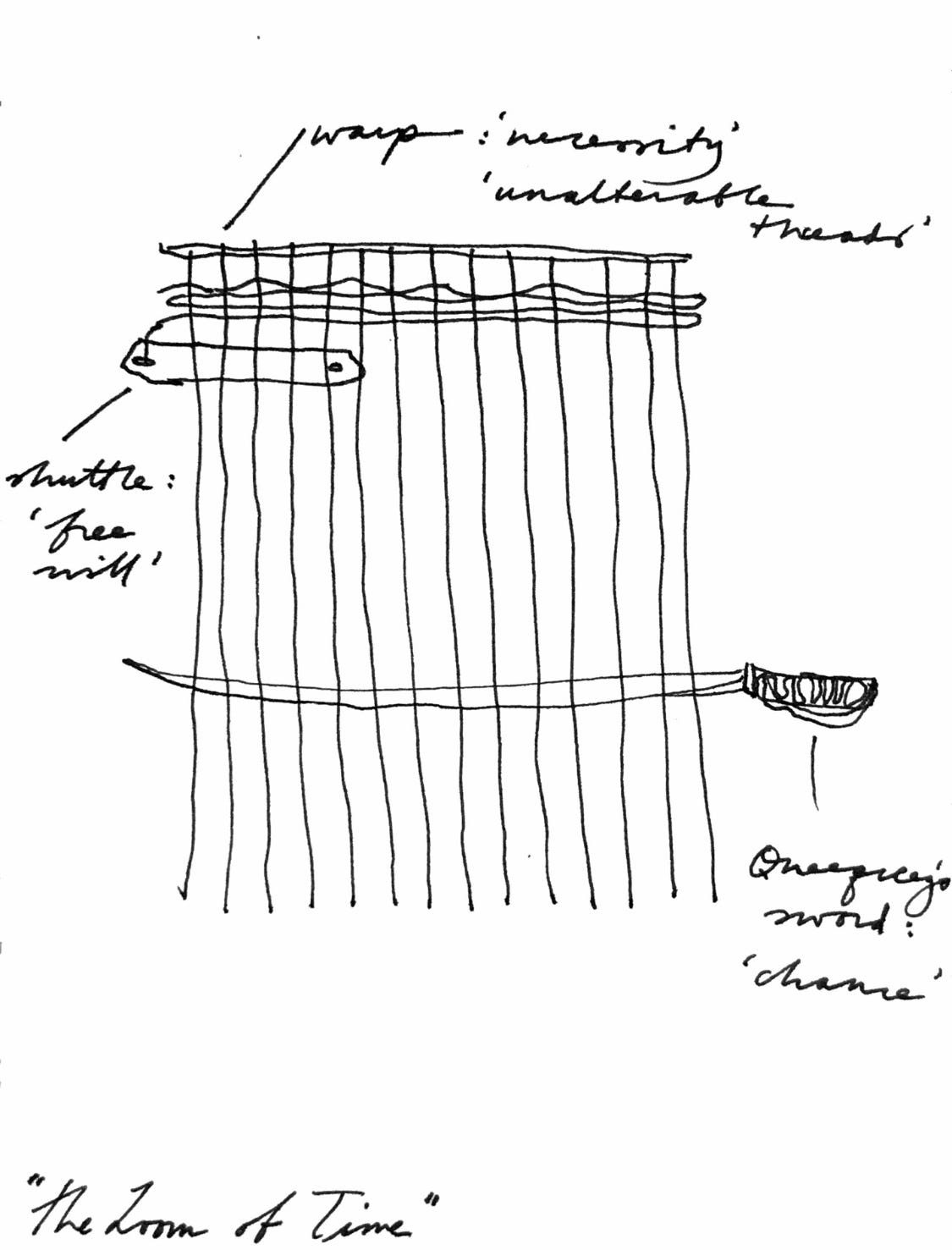

II. Melville figured out, in a paragraph, the seemingly irreconcilable ideas of fate (providence, predestination), chance, and free will. A paradox unsolved by Calvinism, Sophocles, or Democritus! Ishmael, the narrator, and his closest mate Queequeg, the experienced harpooner—who also happens to be a cannibal—sit together on the ship’s deck weaving a sword-mat to cushion the spars. Rather than give a tidy summary, I will quote here at length (it’s just too good!):

“...it seemed as if this were the Loom of Time, and I myself were a shuttle mechanically weaving and weaving away at the Fates. There lay the fixed threads of the warp subject to but one single, ever returning, unchanging vibration, and that vibration merely enough to admit of the crosswise interblending of other threads with its own. This warp seemed necessity; and here, thought I, with my own hand I ply my own shuttle and weave my own destiny into these unalterable threads. Meantime, Queequeg’s impulsive, indifferent sword, sometimes hitting the woof slantingly, or crookedly, or strongly, or weakly, as the case might be; and by this difference in the concluding blow producing a corresponding contrast in the final aspect of the completed fabric; this savage’s sword, thought I, which thus finally shapes and fashions both warp and woof; this easy, indifferent sword must be chance—aye, chance, free will, and necessity—no wise incompatible—all interweavingly working together. The straight warp of necessity, not to be swerved from its ultimate course—its every alternating vibration, indeed, only tending to that; free will still free to ply her shuttle between given threads; and chance, though restrained in its play within the right lines of necessity, and sideways in its motions directed by free will, though thus prescribed to by both, chance by turns rules either, and has the last featuring blow at events…”

III. And finally, an idea my mom illuminated for me: Unlimbed Ahab is not out to avenge his deformity! He is the only survivor of a whaling disaster. Ahab’s “three boats stove around him, and oars and men both whirling in the eddies.” This is a line that many readers sail past, but it is worth stumbling over. The two connectives (“and…and”) are strictly redundant—you only need the second one in such a clause. But Melville wants us to pause here, to puzzle over the polysyndeton, because here lies the key to Ahab’s moody one-track mindedness. His men, whose lungs moments ago heaved with life, whose strong arms expertly pulled oars, are now reduced to that very wood. His desperation is full of pathos—he attempts to injure the leviathan, “blindly seeking with a six-inch blade to reach the fathom-deep life of the whale.” Later, reeling from the disaster, “Ahab and anguish lay stretched together in one hammock.” Ahab is not curdling with resentment over his leg; he is mourning the beautiful young mates under his care. His monomaniacal pursuit is an expression of man’s deep longings and irremediable losses and unsoothable pains.

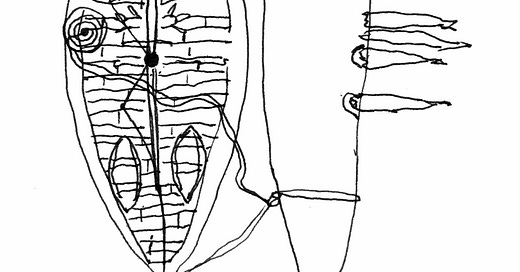

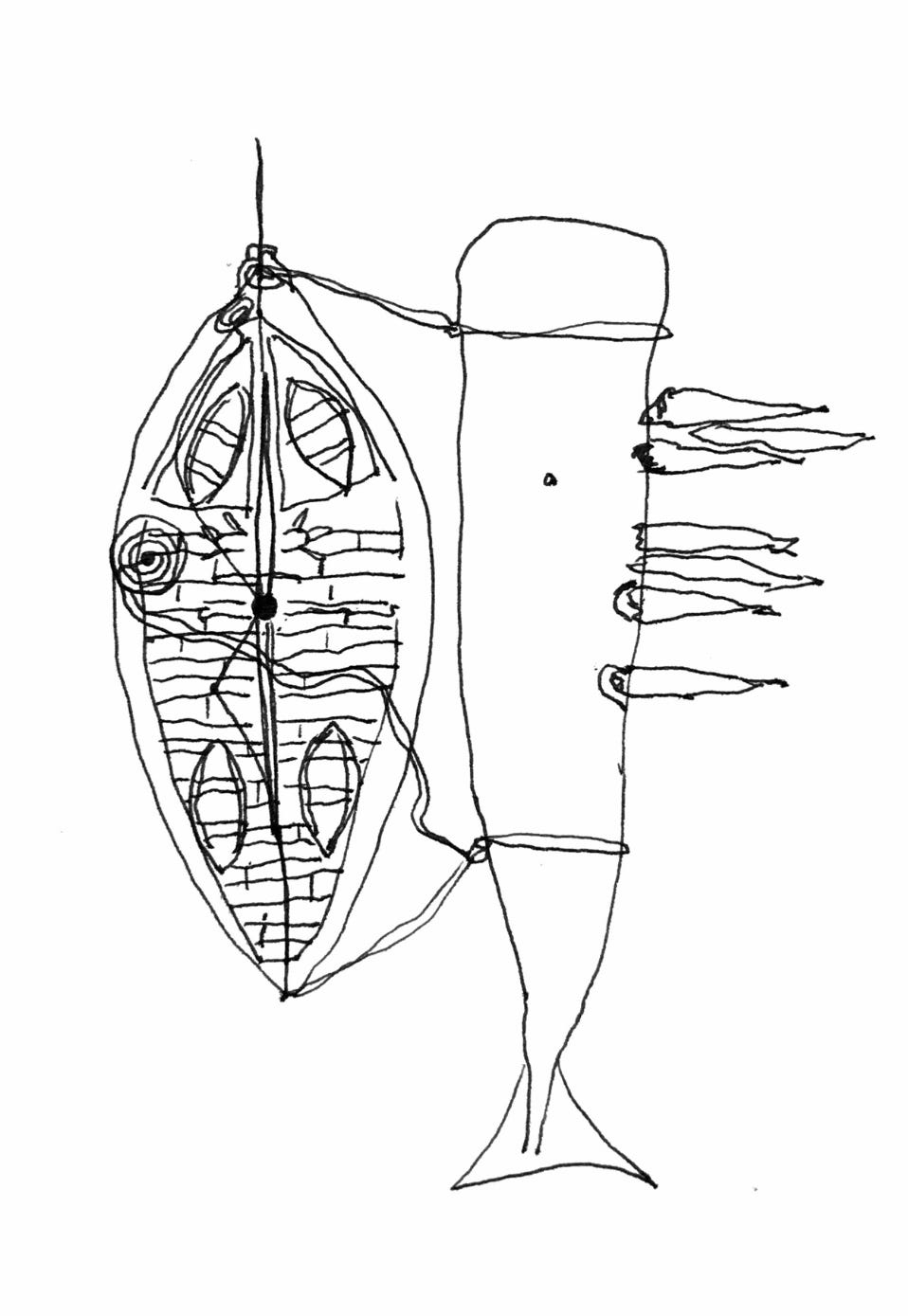

This is how I imagined the Pequod yoked to the sperm whaling ship’s first kill, the whale’s bulk seeming like a second hull, as Melville writes; swarms of sharks taking symmetrical chunks out of the cetacean’s expired flesh.

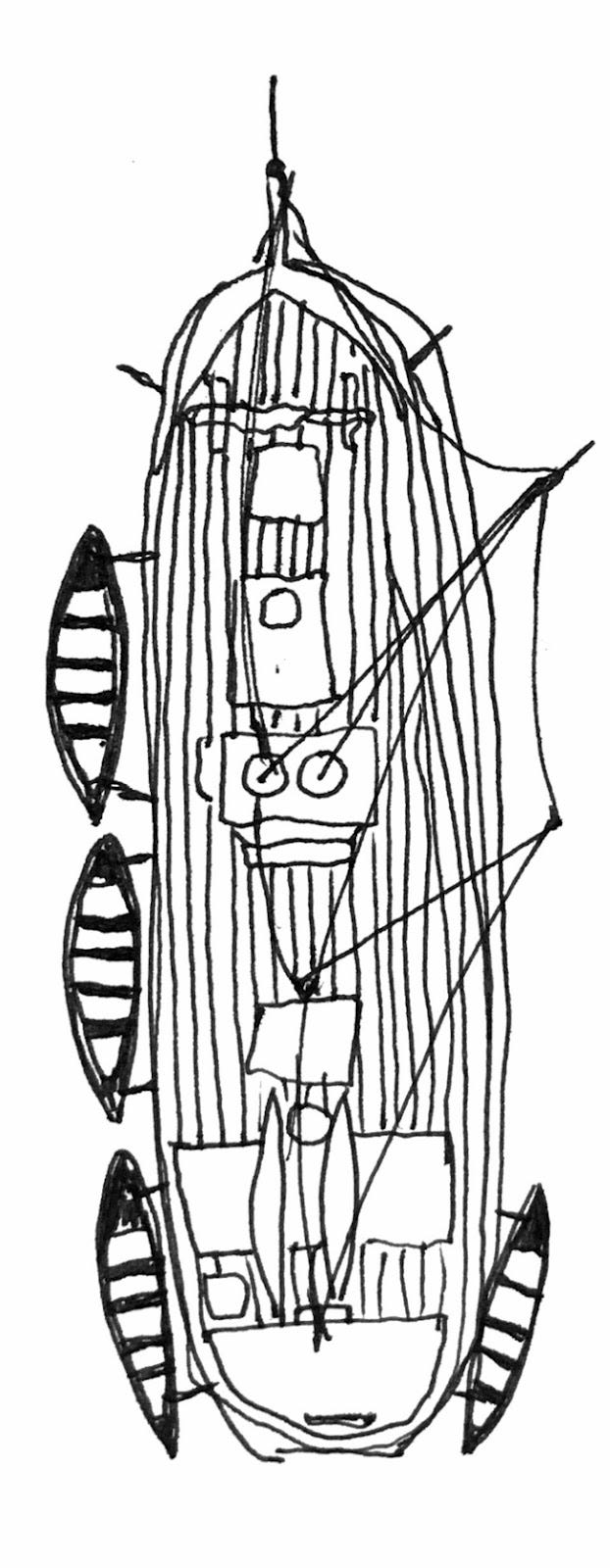

But, as my mom delicately pointed out to me, what I have drawn is a boat, not a ship. Seen from above, a nineteenth-century whaling ship would’ve really looked more like this:

Our Melville Syllabus for the Interested Homeschooler (Or, Lifelong Learner)

I began by reading Melville’s letters to Nathaniel Hawthorne in the white-hot summer of his finishing Moby-Dick. They are a useful portrait of Melville, of a sensibility and a kind of writing that are importantly different from the narrator Ishmael, who eventually hoves out of the reader’s view. Then I read Melville’s only work of literary criticism, “Hawthorne and His Mosses,” a short essay on Hawthorne’s Mosses from an Old Manse. While ostensibly a book review, in it Melville reveals the project of American writers in his century. I followed this up with “Bartleby,” a deliciously ambiguous short story—the first claustrophobic thriller, I’d say. Now introduced to Melville and itching for The Big Show, I started Moby-Dick. Soon I'll start Ronald Mason’s The Spirit Above the Dust, a study of Melville and his work, written in 1951 by my mom’s favorite kind of literary critic—someone who writes for love, not to pad his CV, but with the rigor and precision of a true scholar. We’ve given ourselves about four weeks to finish Moby-Dick, but rather than read at a steady pace, some days I put in long hours and some days I dip in. Every once in a while my mom asks me a startling, provocative question—I might respond to one of these next time.