It’s a good time for reading in my life—a good era of classes, a confluence of interests, a nicely symbiotic collection of important works. On Saturday, I sat down with Plato’s Phaedo in the afternoon and the Book of Exodus in the evening. Sunday morning was given over to Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America, and the Odyssey that night. Actually, it’s all a little too perfect. The springtime game of soccer after dinner didn’t help. “We’re so ‘liberal arts college,’” a friend dryly remarked, kicking the ball across the perfect green.

So American, I thought, in Tocqueville’s French accent. Born an aristocrat, he came to America in 1831 to write about the prison system. He ended up writing about democracy. For seven-hundred pages.

His report is far from glowing. Tocqueville said that Americans, should his humble treatise ever make it across the Atlantic, would despise it at first sight—they do not have ears for a critique of their society. But they would realize, if only privately and reluctantly, that he is right. “If ever these lines come to America,” he writes, “I am sure of two things: first, that readers will all raise their voices to condemn me; second, that many among them will absolve me at the bottom of their consciences.”

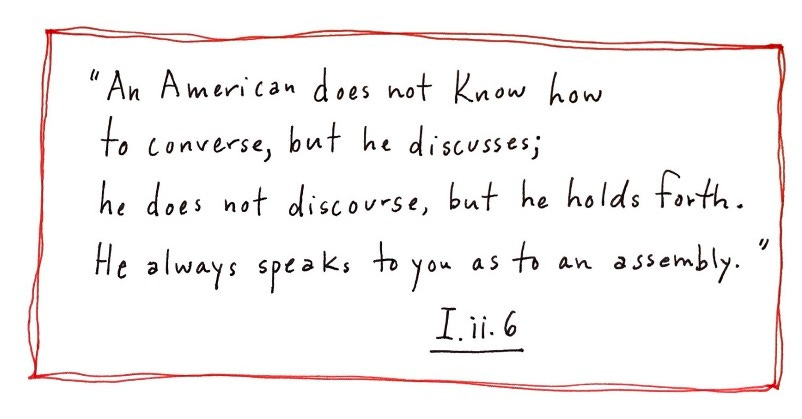

But Democracy in America shouldn’t be seen as a diary of what Tocqueville liked or disliked about America, what he believed in or didn’t support. Rather there are elements of our democracy in which he’s confident, and elements of which he’s deeply suspicious. I mean, the man doesn’t attempt to veil his critiques. He’s like the transatlantic roast comic of the 1830s. (I’ll sprinkle in some of his best take-downs of Americans throughout.)

As far as aristocrats go, though, Tocqueville was very comfortable giving up his patrilineal claim, expecting of himself that he maintain his greatness through real accomplishments. He knows democracy is at once the wise and inevitable option, and yet he mourns the loss of aristocratic excellence—the brilliance, extremity, and energy of the select few. Tocqueville is not divorced from his aristocracy, not wholly disenchanted with it, and he does not suppose it will just melt away.

In his introduction, Tocqueville includes a vignette of a lawful, peaceable society. The passage might first appear to be a description of Tocqueville’s ‘ideal’ society, but this place is by no means a utopia (a ‘no place’). It exists (or at least is firmly on its way to existing) in America. “I conceive a society,” he writes—not ‘I dream up a society.’ He uses the future tense because he sees something inescapable about this new society, a democratic state in which men see the law as their work and submit to authority without trouble. In this democratic state, “if one encounters less brilliance than within an aristocracy, one will find less misery…sciences [will be] less great and ignorance rarer; sentiments less energetic and habits milder; one will note more vices and fewer crimes.” In what appeared to be praise of American democracy, we can recognize an elegy for European aristocracy.

Tocqueville’s melancholic description of a healthy democracy makes the reader long for aristocracy. The democratic state will be “less brilliant, less glorious, less strong…abandoning forever the social advantages that aristocracy can furnish, [society] would have taken from democracy all the goods it can offer them.” The result of equality is universal leveling: men are raised to a certain common level, but they are also cut down to size. “I do not think that there is a country in the world where, in proportion to population,” Tocqueville writes, “so few ignorant and fewer learned men are found than in America.” (Brutal!)

Extremity in belief is undesirable for peace, but requisite for brilliance. Democracy sacrifices the greatness of aristocracy for the goodness of the majority. The merits of a democratic society are its tragedies.

Okay, but why do American college students really need to pay any heed to this—pompous, old, dead, French—man? Because his critiques of Americans in 1830 are weirdly the exact reproaches American college students need to hear today. (And, if we reject the criticisms at first as impertinent, we will secretly acknowledge them in our inward hearts.)

We college students are super guilty of ‘holding forth,’ and not being able to converse. The brightest see conversation as an opportunity to ‘speak to an assembly.’ In a crowd, in a group of so-called like-minded young people, being intellectually independent is tough. People of my age group are especially prone to proceeding by “momentary efforts and sudden impulses.”

Reading Tocqueville is medicinal—at first bitter, then restorative.

Besides, it seems like Tocqueville wants something like a democracy with pockets of aristocracy. Sounds to me like an egalitarian, self-governing country with great universities.

There’s a phrase I love in Democracy in America, which shows up a couple of times: “the shoals of democracy.” These shallow reefs are where democracy goes to die, a ship bashed against the rocks. But Tocqueville also uses the metaphor of shoals to describe the necessary barriers which productively inhibit democracy’s worst tendencies—the rocks over which the massive wave breaks before it can devastate the beach.

At its best, college is the shoal over which the devastating tide of democracy disperses. Ideally, students learn how to converse, not “discuss.” We learn to be alone in a crowd. We gain a little more equanimity and lose a touch of capriciousness.

So, yeah, reading these old books and passing a soccer ball around is very “liberal arts college,” very American. But maybe that’s not such a bad thing.