Sanford Meisner and Dennis Longwell’s book Sanford Meisner on Acting (1987) reads like a Platonic dialogue. It’s not the “creative textbook” on acting Meisner set out to write. He threw out that version. He “was bitterly disappointed at the results” of trying to transmit his “method.” “My basic principles were now on paper,” he confesses in the preface, “but, paradoxically, how I uniquely transmit my ideas wasn’t sufficiently apparent. My students weren’t in those pages either, nor was the classroom in which we interacted week in and week out.” So he started over and wrote a very different kind of book.

What Meisner was most suspicious of was the rule-based teaching (“that semi-intellectual manipulation”) one finds in college drama departments and the acting schools. The book he ended up writing is not a manual on acting technique with clear maxims and lessons. It comprises dozens of scenes, transcribed classes held at the Neighborhood Playhouse where Meisner taught generations of actors, skillfully stitched together with minimal commentary. In the first version of this book, “the drama inherent in our interaction, as they struggled to learn what I struggled to teach,” Meisner writes, “was missing. I came to realize that how I teach is determined by the gradual development of each student.” But the reader of Sanford Meisner on Acting, precisely because the acting “lessons” are offered in the form of dialogue, of human interaction, must work through what the students in the class were working through. Each chapter contributes to the gradual development of the student in the classroom and the student reading the book.

It’s hard to say exactly what Meisner’s method is because it’s not prescriptive. Puzzlingly to an actor fresh out of drama school and blundering into the Neighborhood Playhouse in New York City anytime from 1935 until Meisner’s retirement in 1990, there doesn’t seem to be a script. This is the reason I say this brilliant book reads like a dialogue between Socrates and his interlocutors. Somehow the Meisner Technique emerges in these interactions taken as a whole and can’t be pinned down in formulaic language.

Meisner was known for telling his students not to rely on precepts. “Don’t agree with me. Do it!” is a frequent refrain. “Acting is doing, and meaningful acting is doing under emotional circumstances,” Meisner says to a student who asks him about the difference between action and emotion. The student challenges him: “I thought you said imaginary circumstances.” Meisner replies without missing a beat, “It’s all imaginary.”

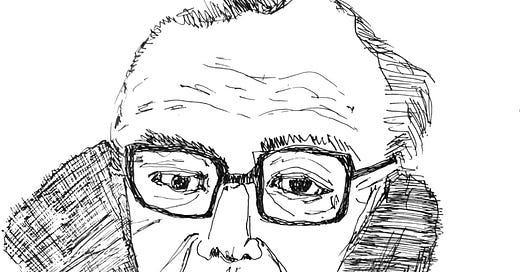

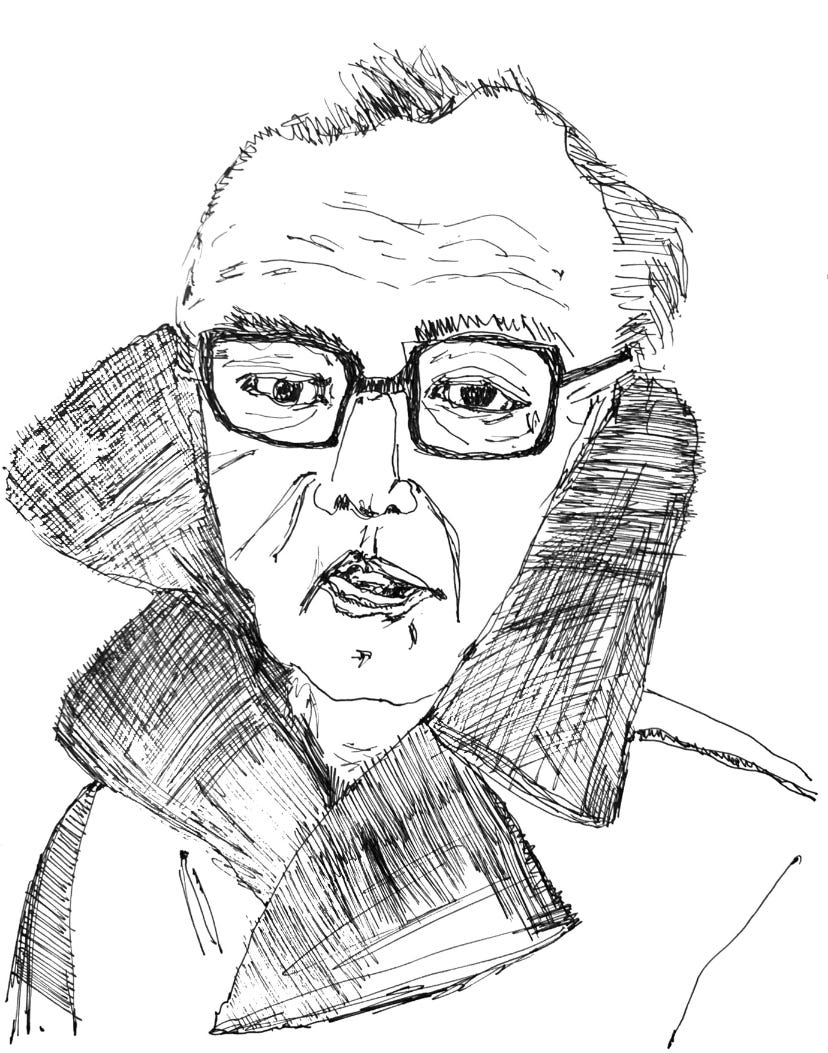

The director Sydney Pollack said the first year of Meisner’s program was all about unlearning the bad habits you came to the studio with. As the actor Eli Wallach says in the documentary, “what Meisner was able to do diagnostically was what was so brilliant about him. He takes you down to a certain level, and then slowly, with these exercises, builds you up so that you are a craftsman.” In other words, he strips away what you thought you learned in school and then spends an enormous amount of time with you figuring out the truth of acting. Like any great teacher, like Socrates, he reveals that you really don’t know that thing you thought you knew. But, happily, that thing is not unknowable.

So why am I writing about this book on acting (of all things) that came out four decades ago? Fair question. Well, a few weeks ago I decided I’m going to be an actor. (Anyone made dizzy by the financial irresponsibility of my choice to be a Classics major has now officially fainted at this even less prudent option!) Thing is, it’s not something I’m counting on, not nearly—it’s not safe, it’s not remotely realistic. I’ve never even acted before. But despite its rocky nature, the idea of being an actor has given me a weird sort of steady footing. Somehow ‘deciding to be an actor’ has given my interests a sort of cohesion. Suddenly my deep interest in movies and the theater, compulsion to imitate people and their accents, love of reading aloud and making up stories, and talking to people about what texts mean all make sense!

I picked up the Meisner book in the acting section of my college library, which is directly opposite from the desk I like to sit at. Just the previous day I had thought, in a seminar on The Tempest, “I could spend my days doing this—thinking about a play or script, working through it with other people, saying it out loud.” I’d never had such a thought before. I get quite nervous at the prospect of doing the same thing every day, forever. So when I sat down at my usual desk I noticed for the first time the small collection of books on acting and the theater. I guess I decided to be an actor when I pulled that Meisner book off the shelf.

What would Meisner say to all this? If acting is doing, can one learn to act from a book? Well, I say, he wrote the book the way he did for a reason. He figured out a way to “uniquely transmit” his ideas in the form of dialogue. For me, the reader in her armchair, it’s imaginable. Reading about acting is learning to act because “it’s all imaginary.”