How do we learn what Raimond Gaita calls “our sense of the preciousness of other people”? is the question I left for myself to answer from last week’s essay. My mom and I talked about it on various dog walks, as we do, and we agreed that the ability to transcend the limitations of perspective usually comes from reading books—or as my mom says, paying close and detailed attention to actual texts. No cleverly written opinion piece has literature’s power to move and change us. The function of great literature “is not to impart Great Truths,” as Bernard Harrison writes, “but to unhinge and destabilize them.” What a work of literature “has to say is never ‘this is how it is,’ but always, rather, ‘might it not be otherwise than an unwise and hasty confidence leads you to think? Might it not be…like this?’”

I’m still learning the preciousness of other people. The fact that I might move quite far away from my family in mere months is making me acutely aware of their preciousness. The next step for me is to act with the recognition that this period of time is coming to an end—to stop whinging about the future and live in the moment. I’m a natural complainer, so this is hard for me.

Listening to David Brooks on Sam Harris’s podcast last week, something stuck out for me amid all the insightfulness. Brooks notes that, “One of the things that did not exist in the ancient world was the notion of compassion.” But, Brooks, dear fellow! Are you taking into account ancient literature? There is a scene in the Aeneid—which Vergil wrote over two thousand years ago, working within and against the Homeric tradition—that I believe utterly refutes this view of an unsympathetic ancient world.

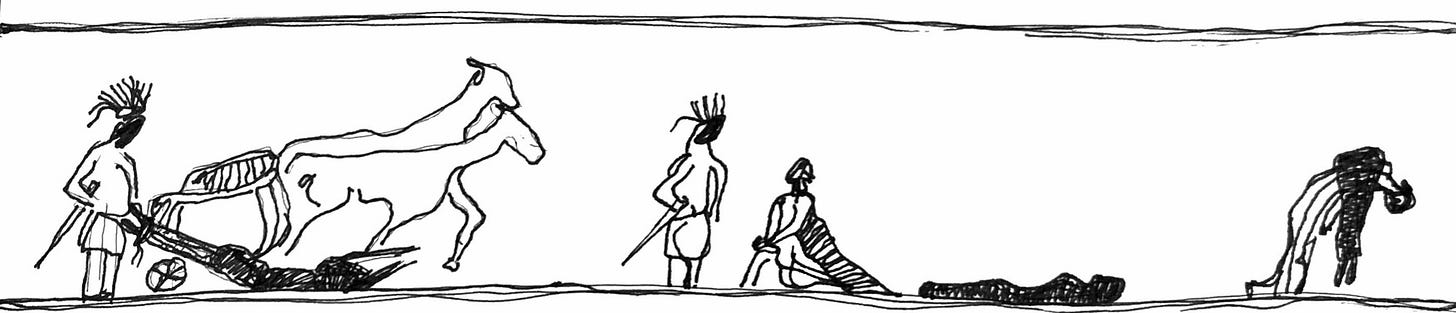

The lost Trojan stumbles upon the new North African kingdom: Aeneas has wandered for seven years before he comes to the temple of Juno in Carthage. He fled the flaming citadels of Troy with twenty ships; he now thinks the tempest has claimed them. Aeneas is displaced in time; as Frederick Ahl writes, “he is looking at a city founded five hundred years after Troy’s fall,” a city patronized by the goddess who has balefully wrecked his ships and kept him from the fated shores of Italy. So he doesn’t expect that her temple, in this strange and hostile land, will receive him on friendly terms. Readers share Aeneas’s surprised when he sees, engraved on the bronze temple doors, “the old war” and the deeds of Trojans set down by sympathetic hands:

“What spot on earth,”

He said, “what region of the earth, Achates,

Is not full of the story of our sorrow?

Look, here is Priam. Even so far away

Great valor has due honor; they weep here

For how the world goes, and our life that passes

Touches their hearts. Throw off your fear. This fame

Insures some kind of refuge.”

trans. Robert Fitzgerald (Aeneid 1.624)

There is nothing more powerful than the recognition and sympathy of your enemy.* Aeneas expects the Carthaginians to be hostile; he himself is jealous of their having land to build on while he is only an exile plagued by the gods. Instead, through the “handiwork of artificers and the toil they spent upon it” he finds his own moving story upon the temple walls.

If the question is “how do you make people more compassionate?” the answer is not by telling them to be compassionate. It’s by exposing them to scenes like this one. The effort of looking closely at a good book (or an especially good film) gives a sense of perspective not your own. Which in turn might lead to a feeling of compassion for someone wholly unlike you, someone you might even think of as an enemy.

*The Turkish memorial to Australian and New Zealander soldiers after the Battle of Gallipoli in the First World War, for example: the men who fought as enemies now lie in rest as brothers.