"Feed Boy," Part Two

Life and death (and WWI poetry) in the chicken coop.

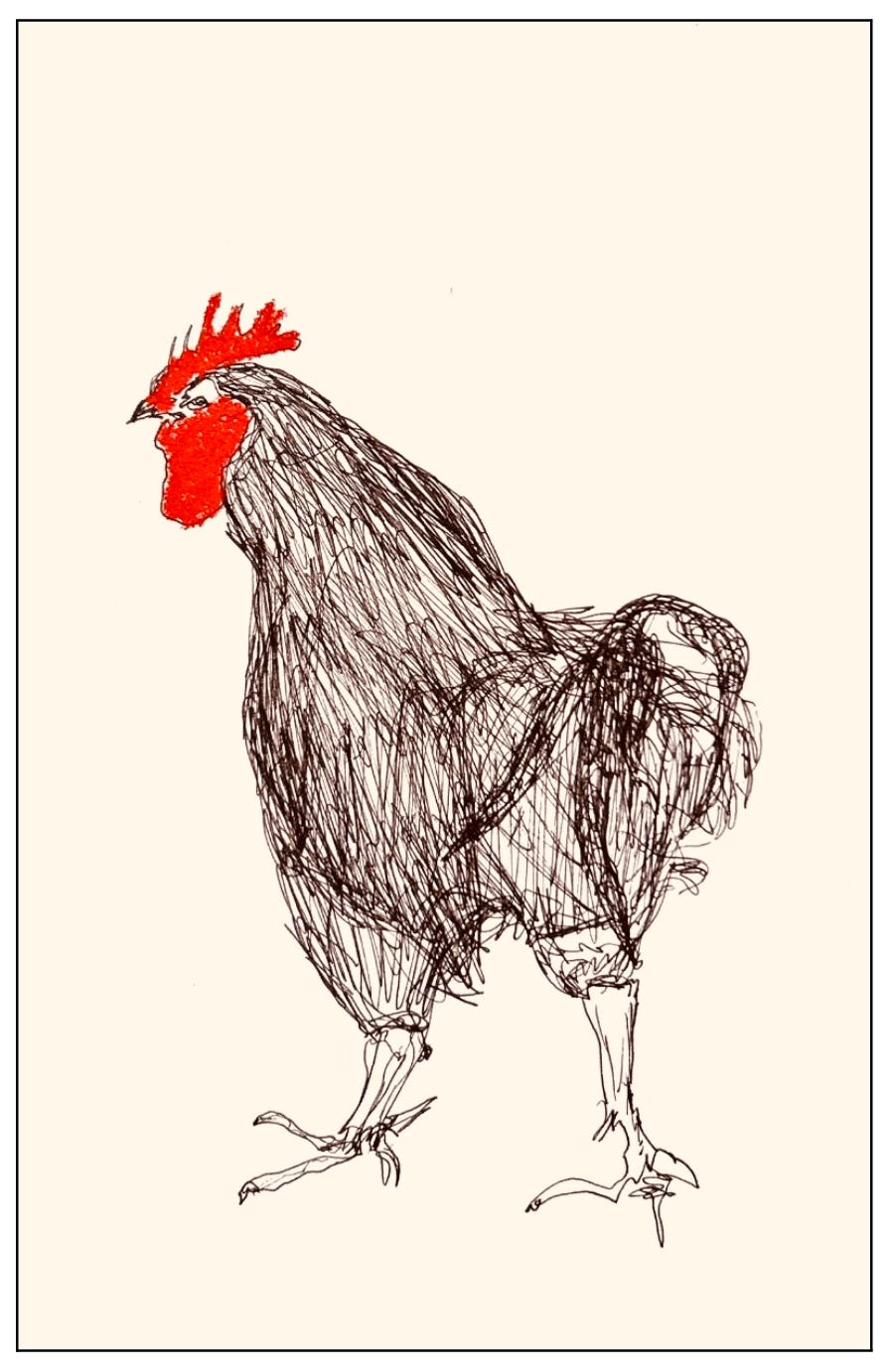

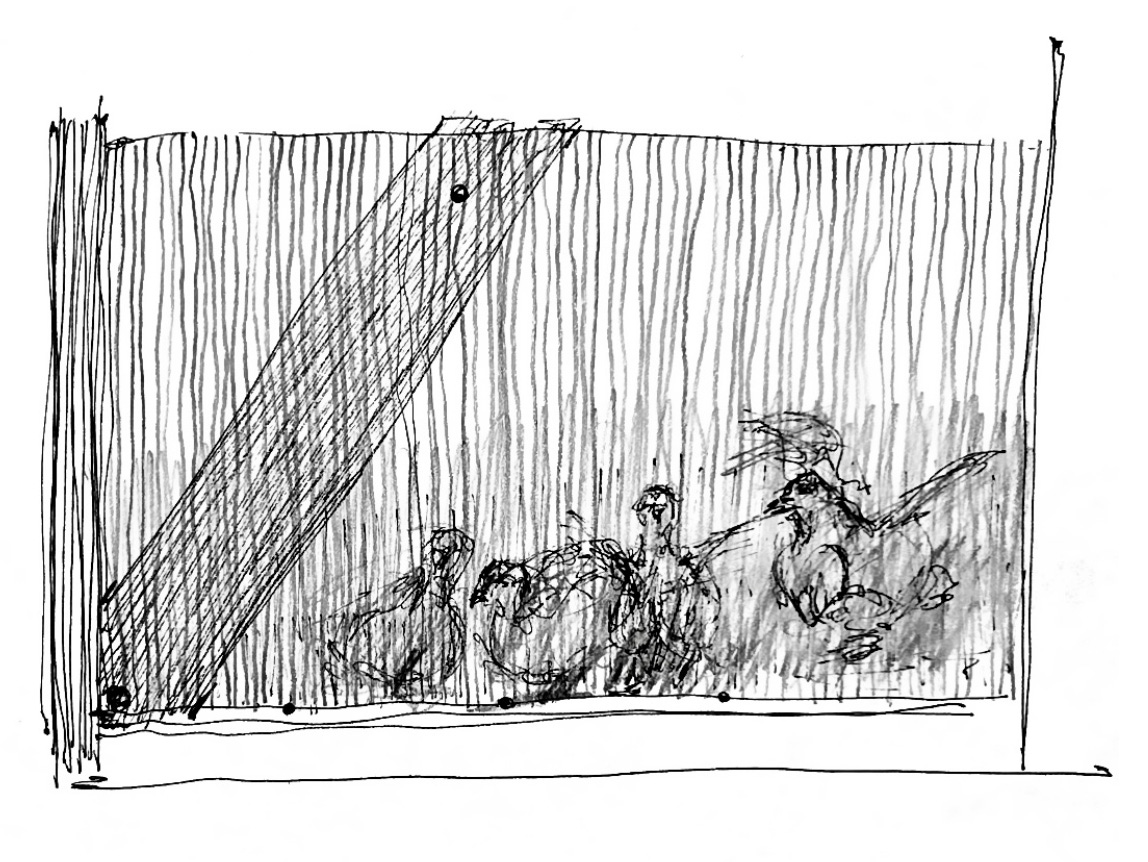

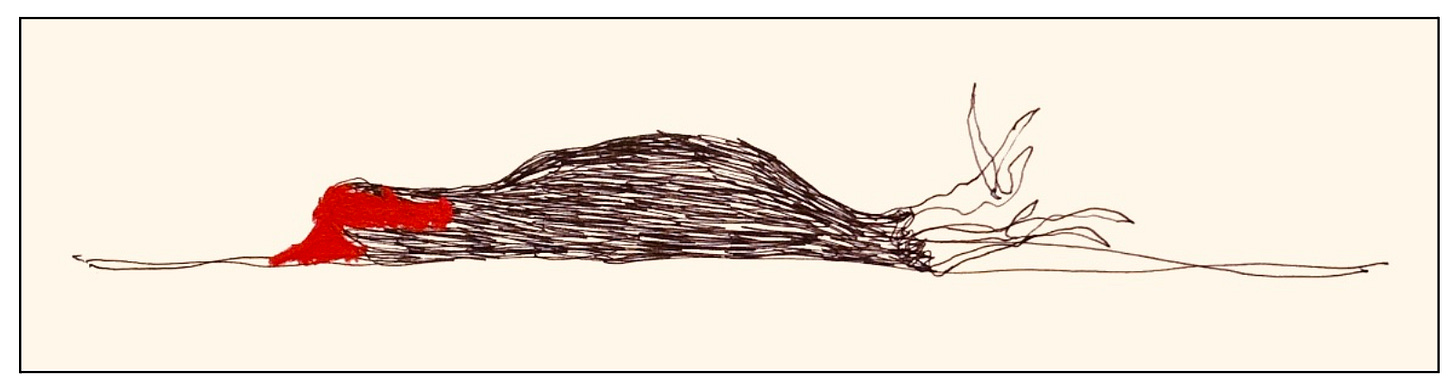

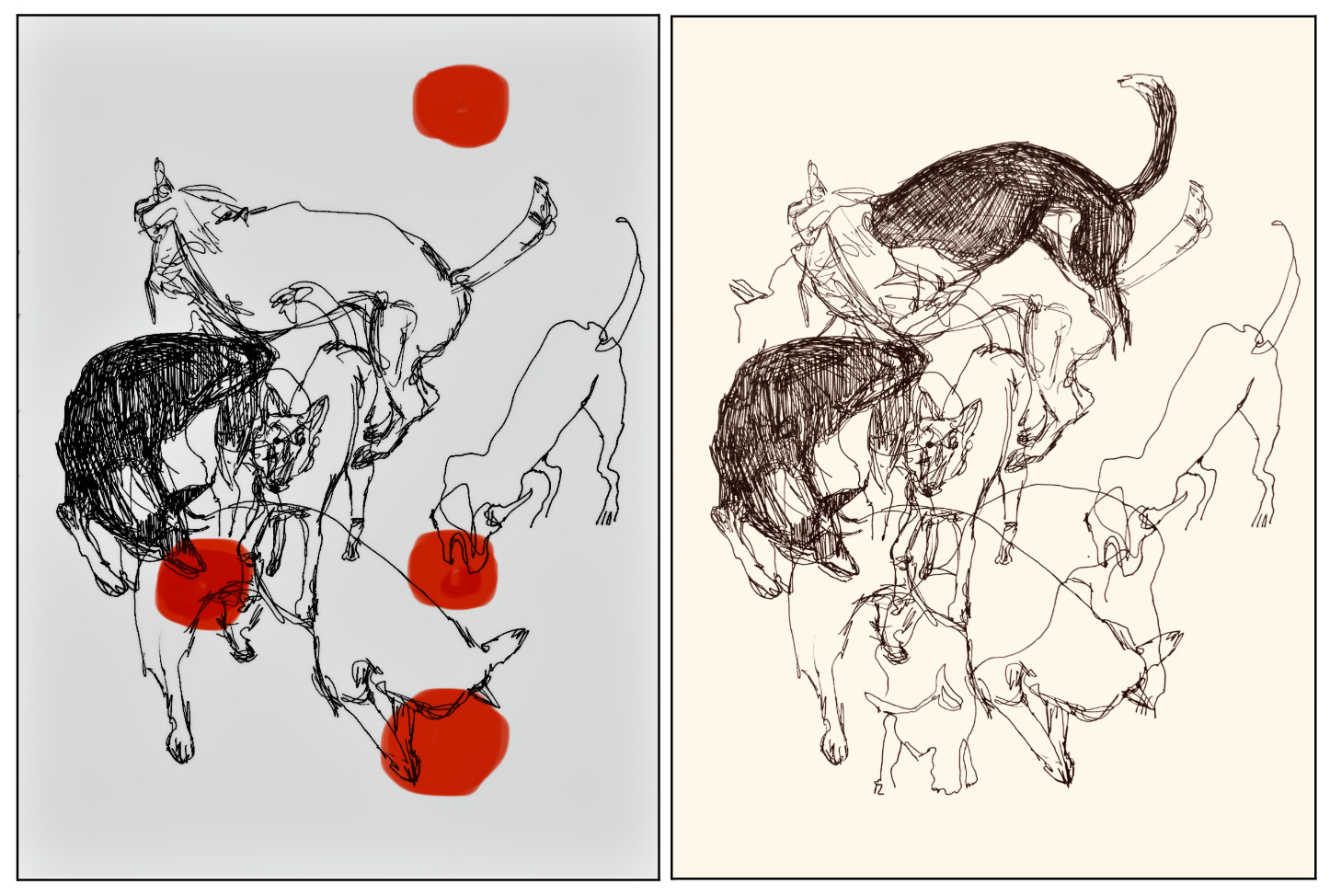

Let me tell you about hens. There are so-called broiler hens, genetically-modified to be constantly starving. In the afternoon they will press against the filmy plexiglass door; the brutality of the scene on the other side is filtered and they appear almost civilized. The white delicate bodies with stubbly skin poking through in same patch on their backs form a seething mass, moving not individually but collectively. They hurl themselves at the feed tray blindly, recklessly, mindlessly. They cannot tell the difference between a boot, a hand, or the tray of pellets. In their desperation for food they thwart the feeder. They do not get this irony.

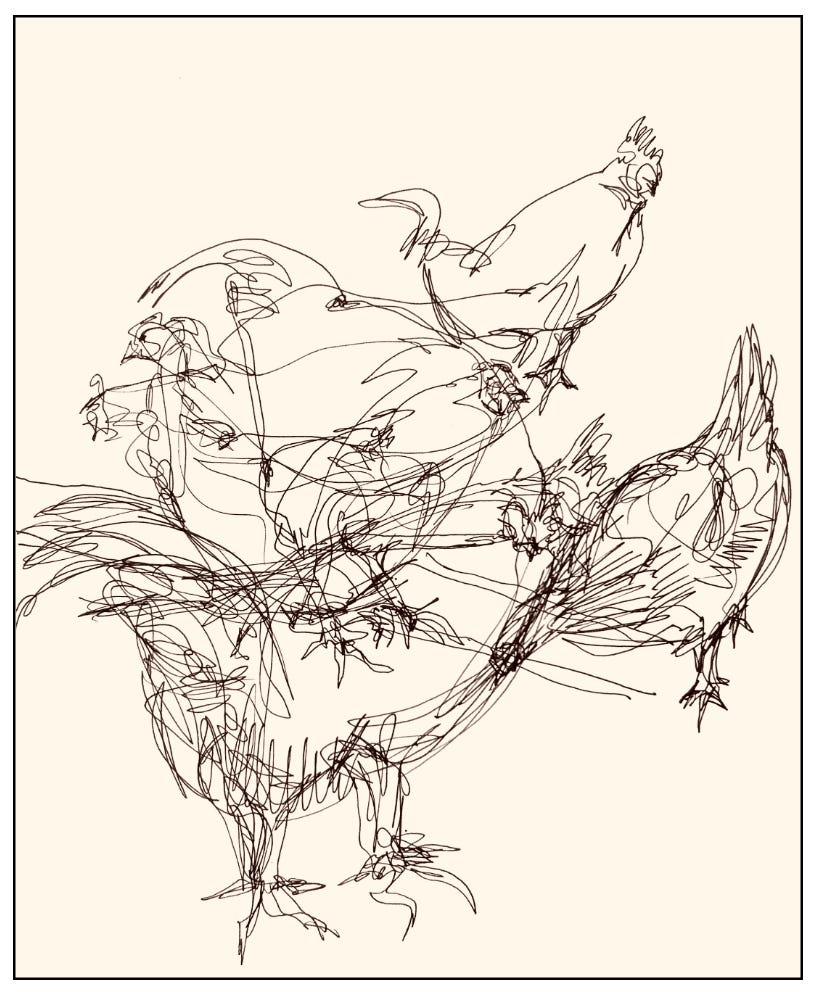

There is the constant danger of stepping on their scaly toes as they swarm. There are strategies for filling the trays: on the one hand moving exceedingly slowly, not raising feet off the ground but dragging them, or on the other moving terribly fast, running around the undulating mob, skirting the throng before they know what’s going on. Broilers arrive as chicks, myopic downy things unaware they must eat and drink to survive. Their endearing infantile sightlessness matures and hardens with their beaks. When the food is gone, they go still, dormant, like movie zombies. They live in a coop which smells of overripe apples and ammonia. They will soon be eaten.

Before being tasked with feeding them, I had only ever encountered these chickens in the death cones, minutes before they were eviscerated. I had gripped their legs and pinned their wings and turned them upside-down and pulled the necks through the hole and fought their kicking legs and beating wings as the red slowly dripped out of them. I thought this was the most brutal thing that could happen to them. That was when I didn’t know anything about chickens. I didn’t know the roosters use the water drip mechanism as a perch from which to pin an unsuspecting thirsty hen to the ground.

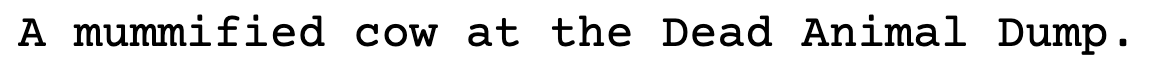

There are layer hens, too. Sometimes they get over the fence into the broiler pen and peck one nearly to death. There was one the other day that I found with half his back missing from being cannibalized. I saw exposed a piece of flesh alive that I’d only ever seen dead. I called him Assless Chap, fed and watered him and kept him warm with a little yellow space heater in a bathroom. He could not overcome his wounds and died in convalescent care.

The layer hens, in addition to brutalizing the broilers, produce eggs. I collect eggs in great quantities every afternoon. The first time I did it I kept saying out loud, The miracle of life! The miracle of life! Yesterday I had collected most of them when I saw a dead rooster under the roosting apparatus. Death, I kept muttering, death next to life. The obscene bucolic. Eggs, still warm. Chicken, cold stiff deflated.

I have found this brief period of work with animals (soon coming to an end) to be surprisingly exhilarating and upsetting. I didn’t realize it would affect me so much. It didn’t help that I was reading about artists at the front in World War One. In this novel, Pat Barker’s marvelous Life Class, a young painter volunteers to nurse and drive ambulances in Belgium in the early days of the war.

I am not so vegetarian as to compare the brutality of the chicken coop to the front lines of a world war! But I realized, in my very limited range of experience, the chicken coop is probably the closest I’ve come to that uniquely wartime experience of life and death rubbing shoulders. The sunrise and the horse’s wound. The irony of it all.

The painter in Life Class must nurse back to health a soldier who has failed a suicide and once recovered will be promptly shot for desertion. I couldn’t help but think of my efforts to save Assless Chap, knowing that I was just preserving him a little longer before slaughter.