College or Life in the Woods?

Reading Thoreau’s views of the “expensive game” of higher education.

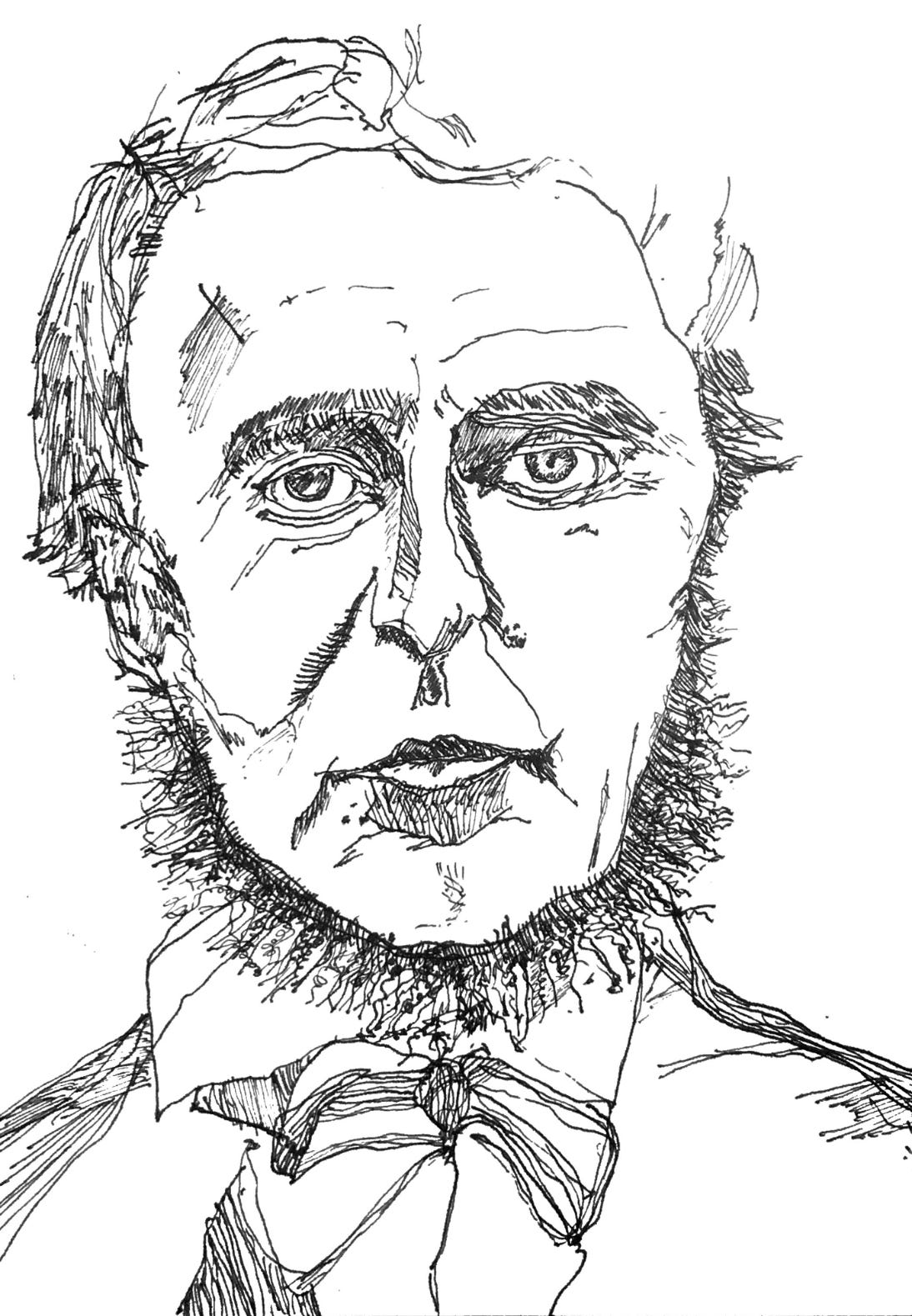

“At Cambridge College,” Henry David Thoreau wrote in 1854 of the school now known as Harvard, “the mere rent of a student's room, which is only a little larger than my own, is thirty dollars each year, though the corporation had the advantage of building thirty-two side by side and under one roof, and the occupant suffers the inconvenience of many and noisy neighbors, and perhaps a residence in the fourth story.” Earlier in Walden he pointed out that it cost him twenty-eight dollars to build his own—secluded, comfortable—cottage, somewhere he could live his entire life. A year’s college accommodation is near equivalent to a modest home in cost, and far more transient, shared, and shabby.

A whole thirty dollars for all of my college! Where do I sign, Mr. Berry Gordy? (In my best John Mulaney voice.) Thoreau’s idea of an exorbitant fee is equivalent to a little over a thousand dollars today. That won’t get you far in a world in which Vanderbilt’s fees have surpassed one hundred thousand dollars a year, and other private universities are not-so-slowly creeping up to meet her. But the point stands, almost two hundred years later: why are students paying a corporation (dressed up as a university) for an apartment (disguised as an education)?

“I cannot but think,” Thoreau continues, “that if we had more true wisdom” and “proper management on both sides” the “pecuniary expense of getting an education would in a great measure vanish.” Moreover, he adds to this already radical statement, “those things for which the most money is demanded are never the things which the student most wants. Tuition, for instance, is an important item in the term bill, while for the far more valuable education which he gets by associating with the most cultivated of his contemporaries no charge is made.”

Thoreau suggests a different course: students should not shirk labor but demand that it be a crucial element of their education. Labor alone makes leisure fruitful. Thoreau ventriloquizes those skeptical of the heuristic value of physical labor: “You do not mean that the students should go to work with their hands instead of their heads?”

“I do not mean that exactly,” he responds to his imagined interlocutor, “but I mean something which he might think a good deal like that; I mean that they should not play life, or study it merely, while the community supports them at this expensive game, but earnestly live it from beginning to end.”

The usual course, he says, is to spend “the best part of one's life earning money in order to enjoy a questionable liberty during the least valuable part of it.” In other words, we amass money throughout our lives to help pay for our deaths. (Digging our own graves is one leitmotif in Walden.) There was an Englishman, Thoreau writes, who “went to India to make a fortune first, in order that he might return to England and live the life of a poet.” But of course by seeking riches for the greater part of his life he had unfitted himself to be a poet. “He should have gone up garret at once.”

So the different course he suggests is not the all-too-common reading of Walden in which one ends up living in the woods—that is, a literal reading by avid but naive readers who pick up bread-making and roof-tiling to emulate (or simulate) the experiences that led Thoreau to write Walden. Thoreau, though sometimes painfully sincere, is not literally prescribing a trip to the woods. He tells us so. “I would not have any one adopt my mode of living on any account … but I would have each one be very careful to find out and pursue his own way, and not his father's or his mother's or his neighbor's instead.”

As Thoreau tries to correct the profligacy and careerism already blooming at elite universities in his day, he does not say to abandon college altogether. He is very bookish—for the burgeoning classicist, Walden is a treasury of classical allusions. (In the first five pages alone, he brings up Iolas, Hercules’s squire; Deucalion and Pyrrha, who echo the story of Noah and his wife; Telemachus’s guide Mentor; and the Elysian afterlife.) He would never have us abandon our books! But he does feel the need for something to change about the way we educate students, treating them like stakeholders in a company instead of stewards of a shared educational project.

The question is, what Chanticleer will crow loudly enough to wake our universities up?

If you’re following along with our homeschooling curriculum, this week we’re reading Walden (obviously) and Stanley Cavell’s critical interpretation, The Senses of Walden (1972).