I used to describe the college application process as “a ways off,” then “looming,” but now it is definitely “omnipresent.” I had to use this week’s Substack to escape the Common App with its prying questions about my personal life. (Most college essays have become about plumbing your emotional depths and waxing endlessly about your community and identity.) I got sick of talking about myself. Gross.

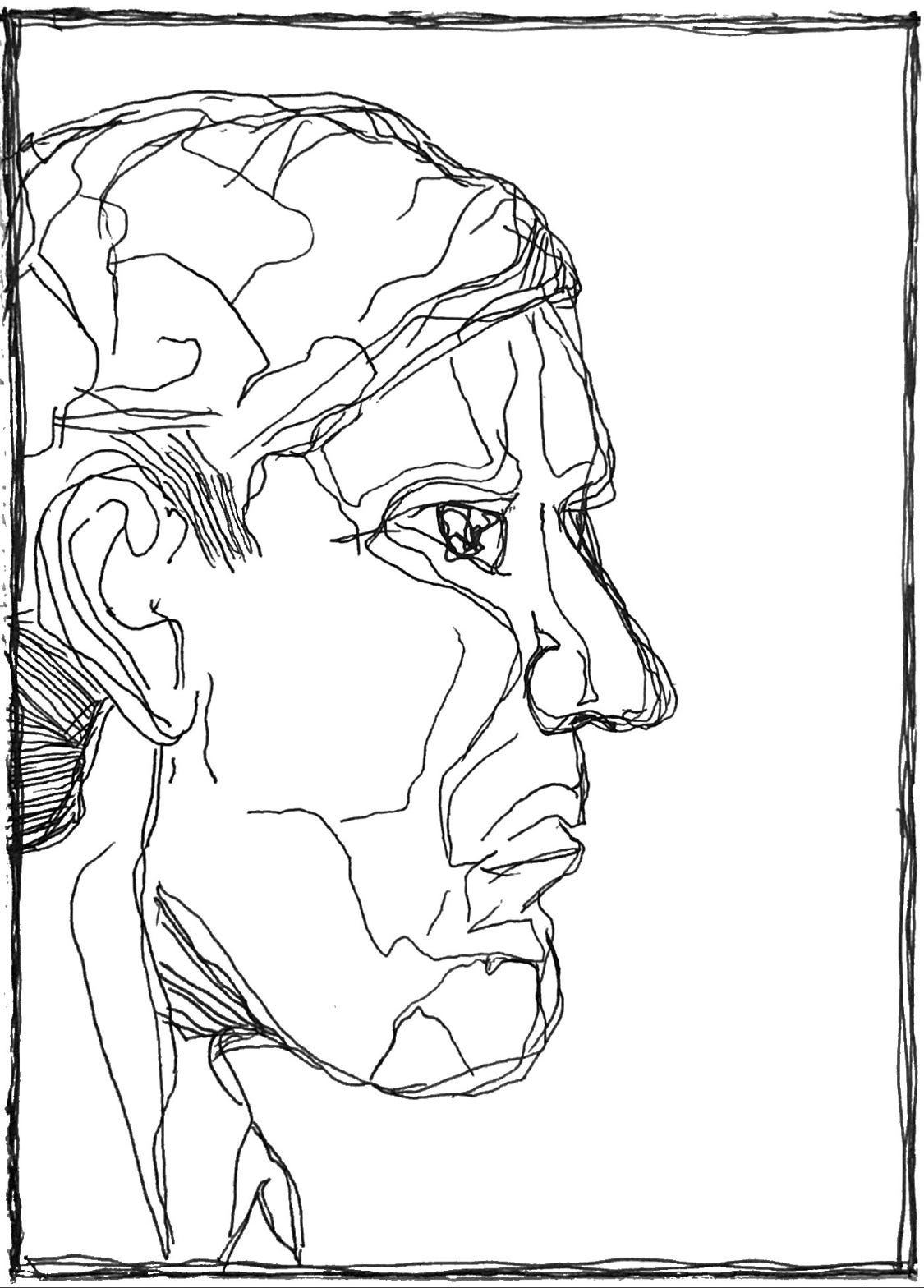

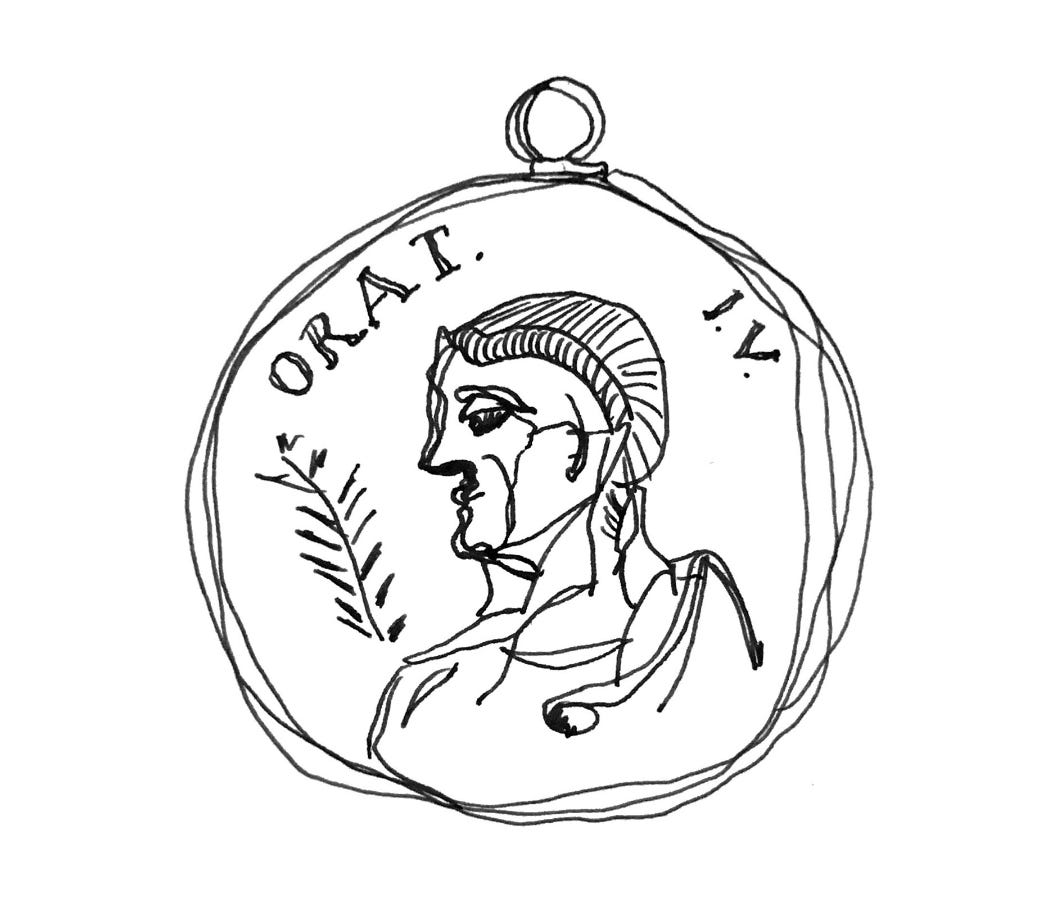

Studying and translating Latin is a pretty good way to bring you out of yourself because it’s so impersonal and so difficult. It’s hard to be self-absorbed (or even self-loathing) when trying to figure out Horace. He died in 8 B.C. and is billed today as one of the great “Augustan era poets” which means he was writing during the reign of Rome’s first emperor, Augustus (Julius Caesar’s nephew and adopted son). My favorite description of Horace (by Llewelyn Morgan, a professor of Latin literature at Brasenose College, Oxford) is “a poet for the middle-aged.” Keep an eye out for Professor Morgan’s upcoming Very Short Introduction to Horace.

And while I am seventeen, I’ve always looked forward to middle-age and senescence and my daily practices would suggest an affinity with the elderly. (Tea, baths, kvetching, PBS dramas, etc.) So I love Horace.

The following ode, the first of book one of his collected odes, is about how it’s hard for poets to conceive of people who like to do things that aren’t poetry. I guess some people like being statesmen and merchants and hunters? I just want to sit here and write my poems.

Horace begins the poem with an address to his benefactor, Maecenas (a real person in antiquity). There are several instances in the poem where Horace uses the second person singular form of the verb (i.e. you are doing something). It’s unclear if he’s still addressing Maecenas or he’s speaking straight to his reader—a typical ambiguity for Horace. He also avoids parallel structure and creates his own meanings for words. He’s unconventional. The original Latin text (courtesy of the Latin Library) comes first and my translation follows.

Maecenas atavis edite regibus,

o et praesidium et dulce decus meum,

sunt quos curriculo pulverem Olympicum

collegisse iuvat metaque fervidis

evitata rotis palmaque nobilis 5

terrarum dominos evehit ad deos;

hunc, si mobilium turba Quiritium

certat tergeminis tollere honoribus;

illum, si proprio condidit horreo

quicquid de Libycis verritur areis. 10

Gaudentem patrios findere sarculo

agros Attalicis condicionibus

numquam demoveas, ut trabe Cypria

Myrtoum pavidus nauta secet mare.

Luctantem Icariis fluctibus Africum 15

mercator metuens otium et oppidi

laudat rura sui; mox reficit rates

quassas, indocilis pauperiem pati.

Est qui nec veteris pocula Massici

nec partem solido demere de die 20

spernit, nunc viridi membra sub arbuto

stratus, nunc ad aquae lene caput sacrae.

Multos castra iuvant et lituo tubae

permixtus sonitus bellaque matribus

detestata. Manet sub Iove frigido 25

venator tenerae coniugis inmemor,

seu visa est catulis cerva fidelibus,

seu rupit teretis Marsus aper plagas.

Me doctarum hederae praemia frontium

dis miscent superis, me gelidum nemus 30

Nympharumque leves cum Satyris chori

secernunt populo, si neque tibias

Euterpe cohibet nec Polyhymnia

Lesboum refugit tendere barbiton.

Quod si me lyricis vatibus inseres, 35

sublimi feriam sidera vertice.

Maecenas, put forth by kingly ancestors,

O! Both protection and sweet honor of mine.

There are men whom it delights to collect Olympian dust

on the chariot and with reckless wheels,

The turning post evaded, and the noble palm 5

Elevated the lords of earth to the gods;

This man—it pleases him if the throng of inconstant Romans

Strives to extol him with reiterated applause;

That man—it pleases him if he stored up in his own granary

Whatever from Libyan threshing floors is swept together. 10

You would never drive out, with obscene sums,

the man glad to cleave with hoe his ancient plot

so that, as a frightened sailor,

he might plow with Cyprian beam the Myrtoan sea.

The trader, trembling before southwesterlies wrestling 15

with Icarian waves, praises leisure and the farms

of his own home town, but soon repairs his shattered ships,

untrained as he is to endure poverty.

There is someone who spurns neither the cups of vintage

nor fails to waste part of the whole day 20

now spreadeagled under the just-green strawberry tree,

now stretched out toward the mild source of the sacred water;

The war camps delight many men—the sound of straight trumpets

mixed up with crooked trumpets and wars cursed by mothers.

The hunter remains under the frigid open air, 25

unmindful of his willowy wife

if a doe by faithful hounds is seen,

or if a Marsian boar through rounded nets has burst.

Ivies, prizes for tutored temples, associate me

with heavenly bodies, and the icy groves 30

and the gentle dances of nymphs with satyrs

distinguish me from the crowd, if she,

Euterpe, does not withhold her flutes, nor Polyhymnia

refuse to extend her Lesbian lyre.

But if you will shelve me among lyric poets, 35

I will, with heady head, collide with stars.

This translation took me several hours twice over! In the first sitting I wrote a completely literal translation of the basic meaning, paying attention to syntax, cases, vocabulary, tenses, moods based on notes from Latin class. In the second sitting, having the benefit of the grunt work in declensions and conjugations behind me, I now tried to preserve Horace’s style. This meant finding words with equivalent meanings but ones that maybe alliterated or were assonant, like his; cutting off a run-on line to mimic where the original lines enjambed; maintaining chiastic (crossed) or synchetic (interlocked) word order whenever possible in English; and highlighting emphasis with italics where the original placement (at the beginning or end of a clause) made Latin emphasis clear.

I should point out a few spots that are especially beautiful to me. No one would force the happy ploughman to abandon his lands for the sea, Horace writes, because he would be miserable for no reason. He uses two different verbs (findere and secet) that have the same meaning, to cleave or plow, one applied to the lands (tilling the earth), the other to the sea (slicing the waves). Earlier in lines 5 and 6, the Latin evitata and evehit chime phonetically; I tried, in translating them, to keep the similarity: “evaded” and “elevated.” (Although, as my brilliant and meticulous Latin teacher Suzanne Nussbaum points out, evehit is present tense, “elevates.”) In the final stanza, Horace uses two verbs quite inventively. Feriam literally means “I will strike” or “I will hit.” Those are the usages we see in the dictionary entries. Somehow neither definition works here, and it isn’t due to Horace making a silly mistake. It is a singular usage. “I will collide with stars” is the best I could manage. Inseres is interesting, too: “You (reader) insert.” But as I recall from a very fun lecture on meta-poetry at Latin Camp, the same verb (insero) is also the technical word for inserting a scroll on a shelf, so I translated “you will shelve,” preserving the implied and highly self-aware double meaning.

And that was only thirty-six lines of poetry—imagine translating an epic poem! (The Aeneid is 9,883 lines.) Cornell Professor Frederick Ahl once told me that it took him longer to translate his Aeneid (preserving the metrical subtleties of the original) than it took Vergil to write it. And it took Vergil over a decade.

There are only a few places where I completely deviated from Horace’s language, and the Latinless reader deserves to know why—since the translator’s role is generally not to explain anything away. In line 8, the phrase tergeminis honoribus could be translated “with triple offices” (three high Roman ranks); “reiterated applause” is the translation suggested by Porphyry, an ancient commentator. In line 12, the phrase Attalicis condicionibus literally means “Attalic terms” which to a Roman reader would suggest riches (King Attalus had become synonymous with great wealth), but which wouldn’t have the same conveyed sense in English. In line 19, “vintage” is metonymy for wine, i.e. using a word associated with the object to describe the object. “Cups of old Massicus” is Horace’s ironically delicate expression for all the wine consumed by the men who spend their days getting “three sheets to the wind” (my favorite British idiom I learned at Latin Camp). I used “vintage” here partly because it’s a nicely archaic euphemism that Keats deploys in “Ode to a Nightingale”: “O, for a draught of vintage!” (a funny exclamation, but the intention behind it, “That I might drink, and leave the world unseen,” is rather bleak).

The Common App form has a section called “Future Plans” in which you have to choose a prescribed type of job. I feel about as excited about those descriptions (Banker to Baker) as Horace does about the other occupations. “Artist of independent means who does some Latin translation on the side and hosts great dinner parties” isn’t an option, apparently. Like Horace, my life is made more difficult by the fact that I am really only interested in literature. It would all be so much easier if I was happy to be a merchant or a drunkard.