It was eleven o’clock on a Tuesday night. I had just submitted the Heidegger paper I’d been working on all that week. I was more than ready for bed but I had to print off thirty copies of Antony and Cleopatra before I could sleep. Rehearsals started the next day, and I was in charge. But I should’ve known not to print large amounts of copy late at night after hours of brain-mangling philosophizing! Thirty copies of each page started dropping into the tray—I had forgotten to collate. I sat on the copy room floor in despair for a while. Then, as calmly as possible, I started making piles of each page, spread in careful columns up and down the floor of the closet-sized room. My dear friend saw my plight and sat down with me, reconciling himself to hours of helping me order the pages by hand. We were more than tired, but we gave over to the misery of the task and had the most marvelous time. We watched the original Muppet Movie and guffawed at the seventies humor and stacked our plays far into the night.

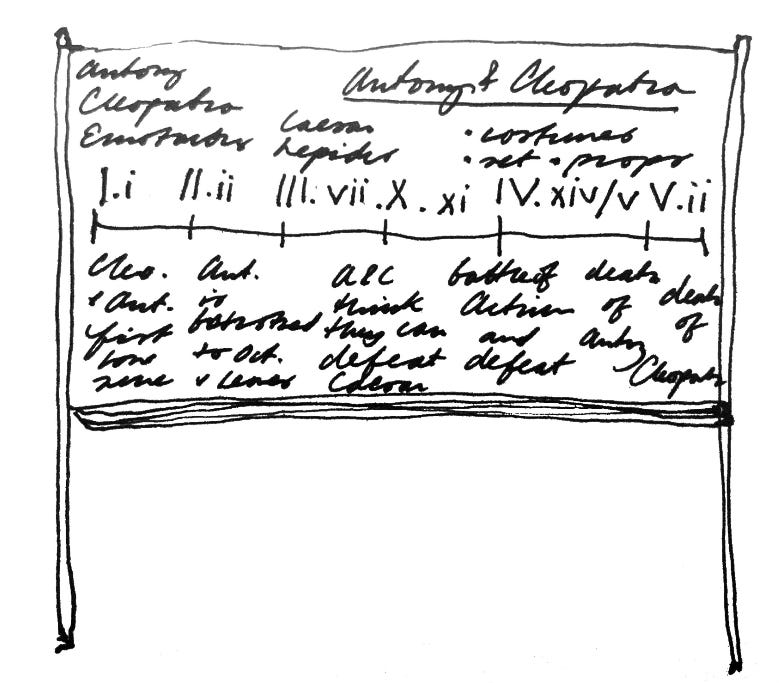

This was the not-so-fortuitous beginning to the three days which I was given to put on one of Shakespeare’s most demanding plays. I and my cast (of under-enthused, overworked, semi-somnolent college students) started reading Antony and Cleopatra the next day. I gathered us in a circle and put a big desk in the center of the room with a scroll of paper over it, littered with pens and scripts and books. That way we could write down our ideas as they struck us and have our notes all together! (Turns out this idea was only exciting to me. Ah well.)

We began reading aloud. I forced us to stop after almost every scene to discuss what happened, what was said, how it was said. A little ways in, something changed. The room was jolted a bit and the confusing Roman history and antique turns of phrase suddenly seemed very immediate and rapturous. Of course as the afternoon went on, and as our other duties began oppressing us, the room sagged and slumped. Suddenly our time was up and we had barely crested Act Three.

The next day brought even fewer attendees and a keener disinterest in the play. My idea of democratically choosing the scenes which were to perform (for we did not attempt the full forty-two scenes) did not work. As one of my actors shrewdly reminded me, “The theater is not a democracy! Be authoritarian.” So I chose the scenes we were to perform, and asked for no more input. It worked! Authoritarianism works!

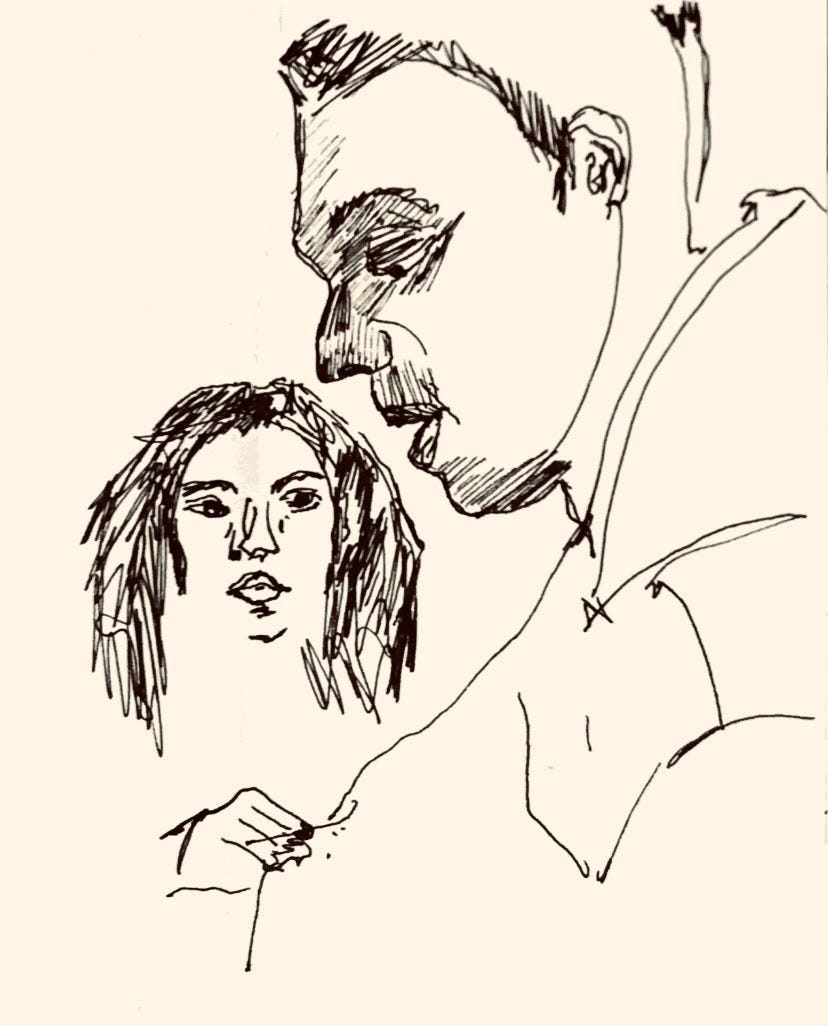

The day we started properly rehearsing was the same day we were set to perform. Under the time pressure, and with the added zest of costumes, our cast of amateurs were enlivened. The dress rehearsal was the first rehearsal—and it was wonderful. Some memorization occurred, but mostly the room was filled with good ideas. We were all invested in these characters at this point; we’d spent hours tracing their narrative arcs and language.

And the set (for which we had no resources, time, or money, of course) came wonderfully together. I dreamed it up. The audience was positioned around the walls of one large room. On one end, a lit fireplace, chaise-lounge, and vibrant silks made up “Egypt.” On the other end of the room, austere red curtains, a war desk, law books, busts, and candles comprised “Rome.” In the middle, the couch was converted to a tomb with a white sheet; the desk’s chair into a prison. A stop-motion with a thousand little paper boats, projected onto the wall, was our naval battle.

Opening (and closing!) night arrived. And, with some whispered stage directions and nudged cues, we made it through. It was so fast and ephemeral and rare. I just want to do things like this over and over again.