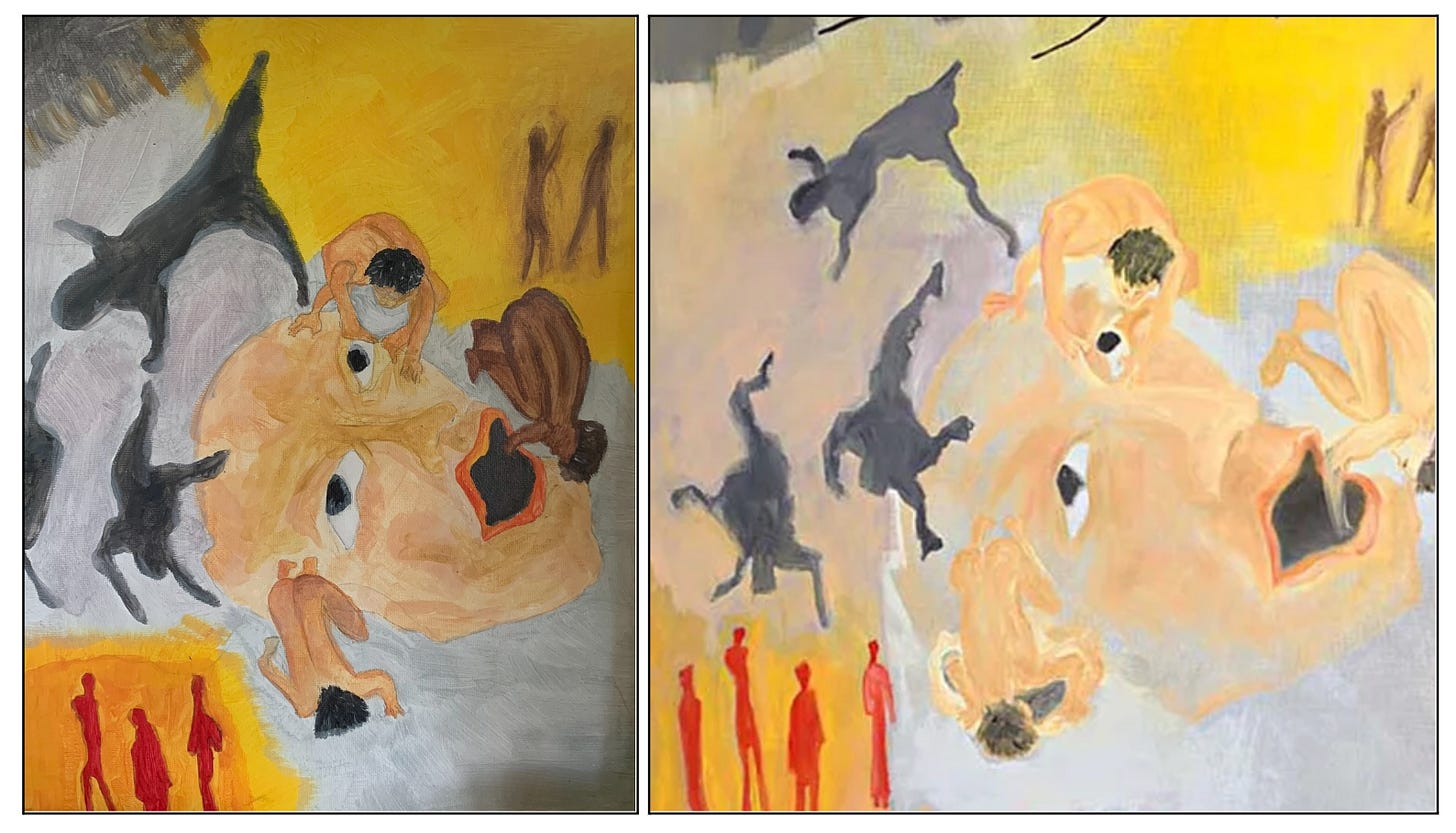

I sent Paul this attempted facsimile of his “Instead of Allegory” (on the right) back in 2020. I had just turned fourteen. A few weeks before Paul had reached out to my mom through a mutual acquaintance. He loved her work on Moby-Dick, he said, and he was an artist working in Santa Fe. They soon became close correspondents, and I fell in love with the pieces he sent to mom. I tried to reproduce one so I could live with it.

The ways in which my copy fails are the reasons why I wanted to study with Paul. My hand was bound and restricted; Paul’s hand didn’t know the traps and restraints of my schoolgirlish trained fastidiousness. Or he had actively unlearned it, as he likes to say. His lines had movement, his empty spaces had meaning, his floating head’s eyes somehow trained in different directions while mine gazed vacuously into space. Of course, I didn’t know how to say that at the time, but I could sense how much was missing from mine, even after hours of careful application.

But Paul saw something in my facsimile that he thought worth spending time on. Every Saturday while we were all house-bound, Paul appeared on my computer screen for hours at a time to discuss art and draw with me and my little sister. Her eight-year-old innovations—staining the canvas with tea bags, mixing her own hair into the paint—always made Paul beam. It took me a lot longer, every session shaking off years of public school art class, but it happened eventually: I drew my first “Ruby line,” as Paul’s phrase goes.

Our first lesson—not really a lesson, as Paul made clear, more of an exercise—was about drawing a circle. We set up a still life with onions, lemons, apples, and oranges, especially the misshapen ones. He told us that Picasso said that if two people draw a circle, each one will be different—and it’s the difference that is art! We drew them from all angles, with our non-dominant hand, looking away from the object, then only looking at it. My circles and lines started to change.

My earliest drawings were just me trying to get out of my own head. Then I started having fun, drawing wild lines, gashes of bold charcoal, and pastel frames. In my “statue drawing era” floating torsos lined my bedroom walls. In my Egon Schiele era (ongoing) I attempted the single line that is “shoulder.” Schiele’s drawings, with their emaciated limbs and hands, led me to the Neue Gallery, where I wandered among his work and elicited curious glances from the guards as I wrote notes and copied shapes.

Paul gave me assignments that were nothing like any assignments I’d ever gotten before. (Once he had me write a quiz for him!) We drew from life, but also from other artists. He gifted me Giacometti, and Diebenkorn, and De Kooning, Schiele, Guston, and Cézanne.

I made these after studying Rita Ackerman and Tracy Emin with Paul (those two contemporary ladies aren’t afraid to draw anything!):

I made these after watching Cuarón’s Great Expectations, and spending most of the movie thinking about Francisco Clemente’s haunting charcoal drawings:

And the “Ruby lines,” as Paul had christened them, came out unexpectedly. After that first intense season of meeting every week during the pandemic, my schoolwork started to take over and it was art that rescued me in the evenings. I wouldn’t draw for weeks, then it was all I thought about. I thought those lines would abandon me, but somehow with the right hand and the right mood I could almost always get to them.

I started pulling out my sketchbook when I was traveling, carting around Paul in my head and pastels in my rucksack. I chronicled Cape Cod and Freiburg; I drew strangers when they weren’t looking. I remembered Paul telling me about the great French artists sitting on street corners and drawing as people moved by. The pedestrians’ movements were helpfully disruptive; the drawings moved now, too.

Paul is the greatest of teachers because he doesn’t think of himself as a teacher. He was a writer for a long time before he became a painter—and he remains a poet. You can hear it in the way he speaks. Never before was I so moved to write down everything someone said. So far I’ve filled three notebooks just with his extemporaneous, aphoristic remarks. And his stories of artists’ lives, remembered from extensive reading, became a part of our common exchange. It doesn’t hurt that he is such a great artist! Great in part because he is brave. He will take a perfectly good drawing and take a tremendous risk with it. He encourages me to do the same. Even if I end up destroying it, as I sometimes do, I never regret it because I know Paul wouldn’t want me to take the safe path.

For Paul, the artistic mentor of a lifetime.

For my dear Stumblers, a new offer, an artistic venture. My experience writing this Substack often leaves me gobsmacked. Twice the usual amount of readers for last week’s Latin translation?! Blimey.

After eight months of publication, with a piece published every Monday, I’m moving to an optional paid model. All musings will still be free for everyone! But…if you opt for the monthly subscription, you’ll receive by mail one of my original drawings or prints. (That’s the plan, anyway; I’m still working out the details!)

I’m also working on reading aloud all my past pieces. These recordings will be available for paid subscribers. Listen below, this time for free, to “A Painter’s Apprentice.”