Yes, I’m still reading The Duty of Genius and I’m drawn to writing about what I’m learning. It’s the kind of book you can’t help but think about when you’re not reading it. Remember how many posts I had about Middlemarch this winter? Of course that was fiction, written in the tightest, tensest prose—language charged with meaning to the utmost possible degree. But the best biographies are also charged by the negotiation between what the subject has to say for him or herself (drawn from correspondence or public remarks) and what is gathered, described, or presented by the biographer on their behalf. This thrashing out of a life’s meaning is what I find fascinating.

Right now I’m puzzling through what Ray Monk means by Wittgenstein’s educational “ideal” and what Wittgenstein actually asked of his students. I think the word “ideal” might be misleading—Wittgenstein didn’t think his different way of conducting life was unattainable, as “ideal” can suggest. As Monk writes:

The ideal that emerges from his teaching, whether in the Austrian countryside or at Cambridge University, is a Ruskinian one of honest toil combined with a refined intelligence, a deep cultural appreciation and a devout seriousness; a meagre income, but a rich inner life.

I find this noble pennilessness dangerously appealing. The pre-professionals and ambitious career-oriented types don’t want me, and I don’t want them either. At seventeen, nearing my high school graduation and first “adult” birthday, I’m quite ready for retirement. All my older friends are retired and they’re certainly “living their best lives,” as my contemporaries would say.

Recently what’s gotten me excited about working, though, is manual labor. This from a girl who spends a good deal of time drinking tea and unblushingly living a life of the mind. My hands are soft. But Wittgenstein’s advice to his students—to be useful, serious, hardworking, unpretentious, and to find a role in which you can be those things without being stifled—is very compelling to me. It’s curious to hear the twentieth century’s most preeminent philosopher tell his best students not to pursue philosophy. His most philosophically promising students—among them Maurice Drury, Rush Rhees, Norman Malcolm—he urged to go into medicine, to work among the unemployed, to plow fields in Soviet-era Russia. (That last one he thought the better of, after visiting!)

My mom reminds me that this was not some way of irritating his starchy Cambridge colleagues or denigrating philosophy. Actually, he cared so much about philosophy, and thought it was such a serious activity that one should only do it if they absolutely can’t help themselves. Philosophy done poorly or faint-heartedly or in the wrong spirit is far worse than doing nothing at all. But there are some things that are helpful, such as fixing people’s bodies. If you can do anything else, do it! he told them. He likes his things done well—everything from door latches to metaphors—and philosophy, above all, needs to be done well.

Wittgenstein really did try to not be such an inveterate philosopher.

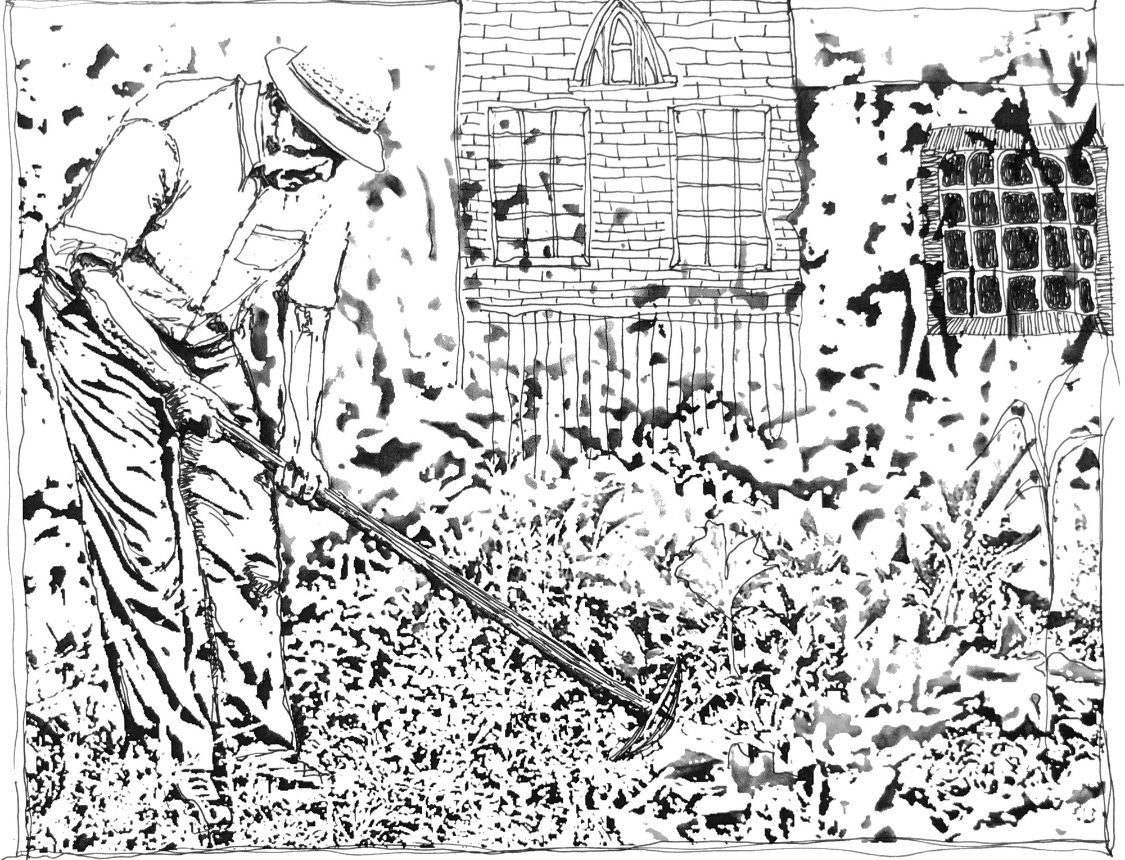

He spent a summer “working as a gardener at the Klosterneuburg Monastery, just outside Vienna. Working solidly the whole day through seemed to act as a kind of therapy.” Wittgenstein told his dear friend Paul Engelmann, “In the evening when the work is done, I am tired, and then I do not feel unhappy.” Gardening, according to Monk, was a job “to which he could bring his customary competence with practical, manual tasks. One day the Abbot of the monastery passed him while he was at work and commented: ‘So I see that intelligence counts for something in gardening too.’ However, the therapy was only partially successful.” Monk attributes his half-happiness to the loss of his beloved David Pinsent.

I think the manual labor had done its work of bringing him back into his body. But he was after all a philosopher and working the whole day through with his hands could only be half of what he needed: he needed brain work too. While feeling the relief of physical exhaustion, he was also being drawn—dragged—back to philosophy.*

Be useful, be serious, be hardworking, don’t be pretentious. Pretty good advice from our friend Wittgenstein. Choosing to work toward being that kind of person is what he means by leading a religious life—conducting your life differently, not talking about religion. Where does this philosopher-laborer life lead, in which I do something practical while I deal with my philosophical and literary urges? I guess we’ll see.

*A Latin side note, for the enthusiast. Wittgenstein’s most important early work, in fact his only book published prehumously (if that’s a word), is the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, referred to as the Tractatus. I realized the other day that this noun ‘treatise’ must originally come from the perfect passive participle tractus of the third declension verb traho, trahere—to drag. In the frequentative form, we get closer to the standard meaning, to handle or treat. But I’d like to think of the Tractatus as something ‘dragged’ out of Wittgenstein.