There is no freedom for me in leaving my family, going back to college. It does not make me feel any more “grown up” to be living without them. When I first got to college my classmates would often comment on my homesickness, almost chastising me for it. “You’ll learn,” an older one said, as if the separation from my family was a discrete skill I could master.

The idea that growing up means getting progressively further away from your family is crap. Total bullshit. On this point, and a few others but fewer than you’d think, I’m anti-Hegel. I couldn’t disagree more with his idea that the family is an institution which anticipates the dissolution of itself—which is designed to break apart, the sole purpose of which is to be a greenhouse for citizens and send its little agents of the family into civil society. (Okay, perhaps a simplistic reading of Hegel’s family, disregarding his lovely idea of ethical unity in marriage and child-rearing—but still!)

This week I was home, shopping for flowers with my mom, helping her plant them, reading political philosophy together in bed. On my way back across the country today, I was panicking about losing her (again). And then I realized: she is never really that far from me, for she’s there in my books. It sounds crazy, but our shared marginalia in books makes her a constant companion. I brought many volumes of hers with me to the desert, making sure to note on the flyleaf that they belonged to her and were just on loan to me.

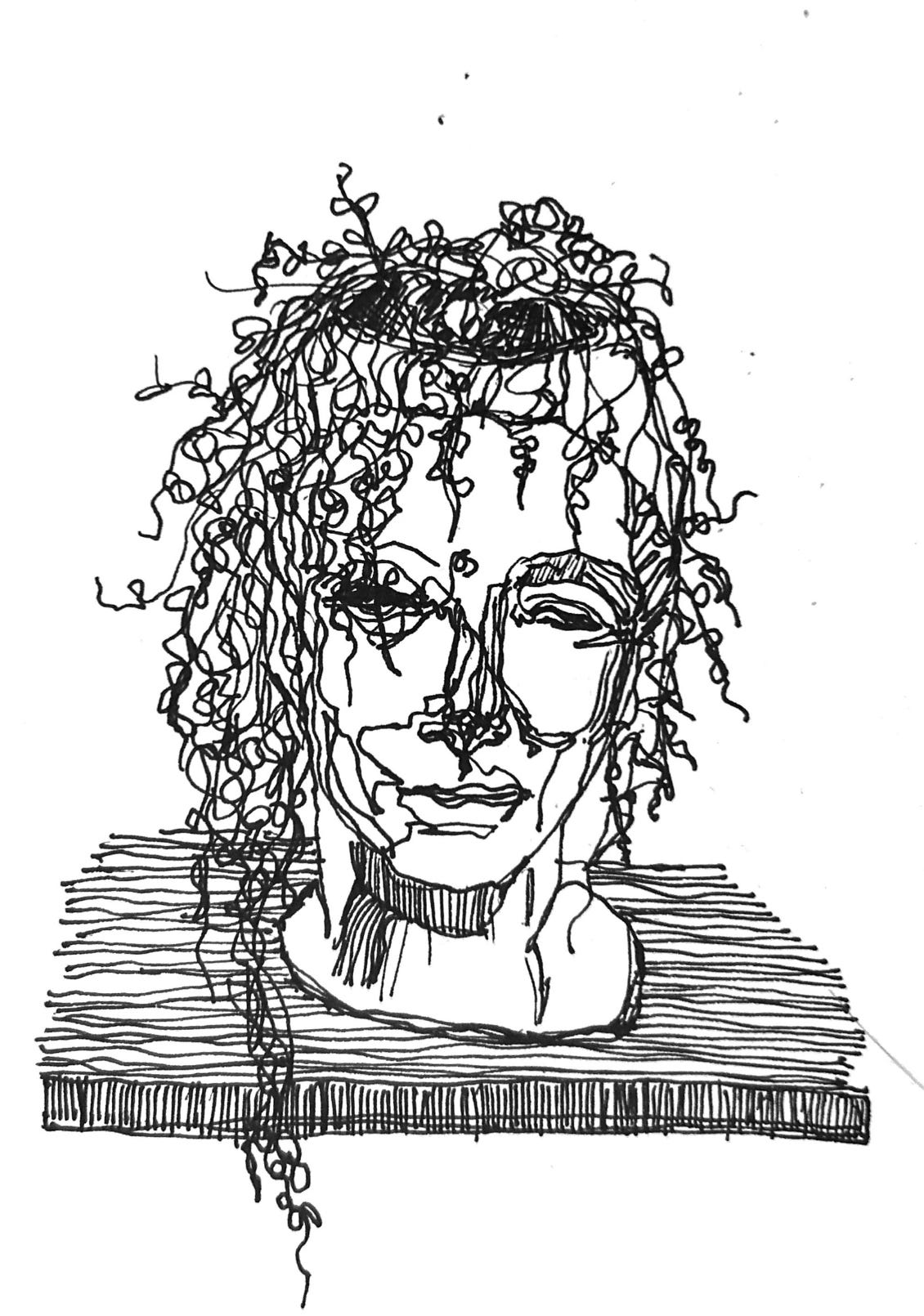

My mother is the origin of my vigorous annotation and compulsive note-taking habit. Our house is filled with her sheets of loose printer paper scrawled on in Precise V5 pens. My notes populate notebooks, but they are just as indefatigable. Our books are similarly scribbled upon.

To the horror of the archivists in my life (my poor dad), there are all sorts of things stuck into my books: dried flowers, letters I will never send, train tickets, tiny sketches. The dog-earing and spine-cracking—abhorred by my father and other careful bookworms—are habits I unblushingly assume from my mom. As for marginalia, I am genetically predisposed to tidy underlines (from dad) and overzealous underlining of entire passages (mom); I reject dad’s sweet use of check-marks, opting for mom’s cryptographic mix of ‘key,’ ‘use,’ ‘hmm,’ and random stars; we all despise highlighters; hard brackets and boxes are rare, and mood-dependent.

The family trait of marking up books and commenting on them nicely parallels another family habit: living on the margins, so to speak. We have a tendency to not do the main thing, and this has led us to the fringe of the academic world.

I have enjoyed living, with my parents, on the periphery of the academy. Unlike Allan Bloom, it was not by popular uproar that my mom and dad found themselves edged out of the profession they had spent a collective quarter-century pursuing. Neither was it entirely by choice. The job my mom loved at a religious and secular university—where she could teach the most studious and devout girls in the city she had always wanted to live in—failed to tenure anyone in the year she was due, as the economy crumbled and literature and philosophy depreciated in marketable value.

When an academic leaves the academy, it’s called “leaving the grove.” That is, the Grove of Dodona, the mythical site of oracular wisdom, transmitted through the rustling leaves of sacred oak trees. But leaving the grove—despite the judgement inherent in that phrase, the implication of heresy, of bereavement of foolishly fleeing the sylvan scene!—sometimes comes as a relief.

Would you want to be a professor in today’s university? I sometimes asked my mom on the homeschooling days when I felt she was disappointed in me, when I could sense her longing for a full classroom where the discussion was so good you forgot about the bad lighting and the shabby carpet. No, probably not, she would beam back at me. But I could tell she was thinking of her best days in the classroom; and it made me long for those lost days.

I’ve been thinking about her life a lot, her teaching life. It’s a life I deem to be of service to humanity, but more importantly, to humans. I’ve been thinking about what it would mean for me to live a life of service. On the plane today, in the back inside-cover of my copy of Bellow’s Herzog, I wrote:

A life lived in the margins of books, I wrote (leaving the end of the sentence to dangle). You give yourself away in that inch between the text and the page’s edge. Marginal doesn’t necessarily mean small or unimportant. Marginalia is framing, intimate, conversational. It is time-keeping and time-capturing better than any journal of events. Marginalia is preserved reactions in real time to the most moving, disturbing, perplexing, insightful moments of a text. It is not meant for public viewership but when one does happen upon the vestiges of life lived in books it becomes a conversation.

Marginalia is like a life of service, how a life of service should be (my notes continue). Private, individual, careful. A display of attention rather than attention-seeking. You can catch glimpses of it—something deemed negligible can be radically intimate, unwittingly incriminating, entirely inconsequential, or the perfect distillation of the product of the author’s thoughts and yours. The notes end rather boldly: a spotless book is a spotless mind. Too tidy for my taste.

“One of the reasons why it’s hard for me to think about going away to college is it’s hard for me to think about learning anything in a place without my mom,” I wrote almost two years ago now, back when I was applying to college. “It’s hard for me to believe I’m ever going to find a teacher as good as her.”

It turns out I don’t need to find another teacher as good as my mom. Because she’s still my teacher, across time and space. She’s my teacher in the margins.